by Mira Tfaily and Jad Baaklini

From April 23rd to 25th, Bus Map Project attended UITP’s MENA Transport Congress in Dubai as part of the regional Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung civil society delegation. Walking around the expo and listening to discussions of futuristic machines and ambitious infrastructural plans left us feeling a bit disconnected from the lived realities and conditions of most people around the MENA region. And yet, we were very happy that, within this dizzying spectacle, the Transport Congress opened up a window to a world that we are very attached to and familiar with.

The Future of Transport?

As we briefly mentioned in a previous post, this year, and to our great enthusiasm, the UITP launched its first Informal Transport Working Group meeting, ever. As the inauguration of what is sure to be a very long discussion, this meeting featured much heated debate, from which we draw some preliminary conclusions: for the most part, the debate around informality in our region is framed within a push for more formality, such that the desire to better understand the informal is almost indistinguishable from the desire to change or “formalize” it. While we welcome any acknowledgement of the realities of transit systems as they actually exist in our societies today, we believe that the stakes are too high to rush too quickly into a “blind” consensus on formalization.

This debate, which left no disagreement untouched, including what to name these unregulated transit systems — informal? hybrid? paratransit? individually-operated? — was a crucial milestone that we are very honored to have contributed to in our small way. It is the beginning of a much-needed conversation in our region, after the informal has demanded a place at the table throughout the world –- and in this spirit, we ask, without presuming to know all the answers: to what extent is the formalization of these networks socially desirable, and to whom? Who is bound to benefit from it, and who is bound to lose? How can we ensure that the most vulnerable populations are not priced out or excluded in the process? And when will it be second nature to have the targets of our policies take part in our discussions from day one?

In order to begin thinking through this batch of questions, it’s important to keep in mind the broader context, and to raise a few more. The theme of the three-day Congress was “Pioneering for Customer Happiness,” which encompassed the two main emerging trends within the MENA transit conversation:

-

a shift in emphasis towards thinking about public transport within the paradigm of MaaS (Mobility as a Service), thanks in part to the rise of more flexible and connected (or app-enabled) mobility options, like Uber and Careem;

-

a shift in emphasis towards putting the satisfaction of the customer at the center of transit provision, with the rubric for achieving this happiness understood through the lens of “innovation.”

In other words, the customer is presented as being generally dissatisfied unless public transport providers start coming up with something new. It’s safe to say that this idea also takes its inspiration from the ‘positive disruption’ that services like Uber and Careem are seen to be providing.

These themes raise a few questions: is innovative infrastructure the solution to what’s at stake for MENA transit? Which customers and whose satisfaction are we talking about, exactly? Can we assume that we all have the same expectations? Can we achieve a socially-just happiness that would benefit all customers, when we are very likely to have diverging interests? And what are the implications of considering people who are mobile in our cities primarily as customers, in the first place?

We believe that answering this second batch of questions goes hand in hand with answering the first batch we raised, on the politics of (in)formality. We will expand on this idea in three moves:

I. Pioneering for Customer Happiness: Innovative Infrastructure or Creative Ways of Thinking?

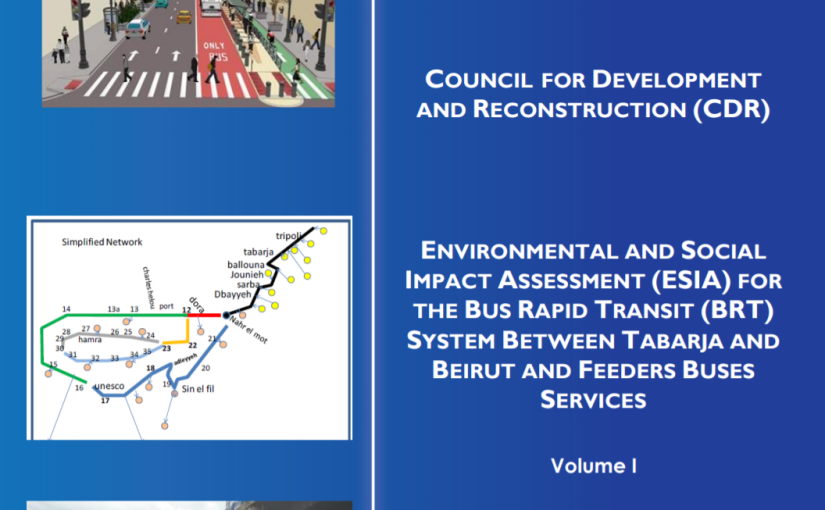

“Customers are the core business of urban mobility.” The opening speech by Pere Calvet Tordera, president of UITP, set the tone for the next three days: a market-oriented vision of mobility that places the notion of customer happiness at the core of planning. To achieve this happiness, innovative projects in the MENA region were showcased throughout the Congress, including Dubai’s futuristic third metro line being built in preparation for Expo2020. It is projects like these that make us wonder what is motivating the push for transit innovation; to what extent do these impressive infrastructural developments meet the actual accessibility and mobility needs of the everyday practitioners of our MENA cities, and how much are their investments driven by a desire to increase a (global) city’s attractiveness, as a travel destination or as part of an international mega-event? The latter may (or may not) be fine in cities like Dubai, but what are cities like Cairo or Beirut supposed to learn from such projects? MENA cities facing multiple challenges have to make wise decisions about where and how to invest.

In the end, building fancier and shinier infrastructure will not bring us closer to the sustainable future we want if this infrastructure does not leave some room for daily usage and affordability within its core calculations, making sure that the most vulnerable populations — who are the bread and butter of mass transit — are not driven out by the gold rush. If we’d rather not call this social justice, then at least let us consider it common sense: why build something that ends up limiting the ranks of your target consumer? Relying on the changing tastes of those with the most purchasing power is not wise policy for systems that are supposedly challenging the king of convenience, the personal car. True innovation requires new ways of thinking.

II. Informal Transportation: a Precursor of Mobility as a Service?

Another key concept deployed throughout the congress was Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). As a market-based vision of mobility, it has the advantage of focusing on the user-perspective, and in so doing, offering more flexible or “adequate” services to the general public. With the arrival of ride-hailing apps like Uber or Careem, some public authorities have scrambled to make love not war by opening up channels of communication and partnership that rethink their very role as transit regulators. This is because these services are increasingly being seen as complementary — or, at least, not inherently antagonistic — to the work of the authorities, particularly when it comes to meeting the “Last Mile Trip” often left out by traditional transit. The logic goes as follows: Fixed-route services like buses typically provide low cost services that move high volumes and are always shared, but they tend to be slower and not always in line with (car-accustomed) customer expectations. Hence, “demand-responsive services” like the new disruptors are increasingly understood as friends of formality.

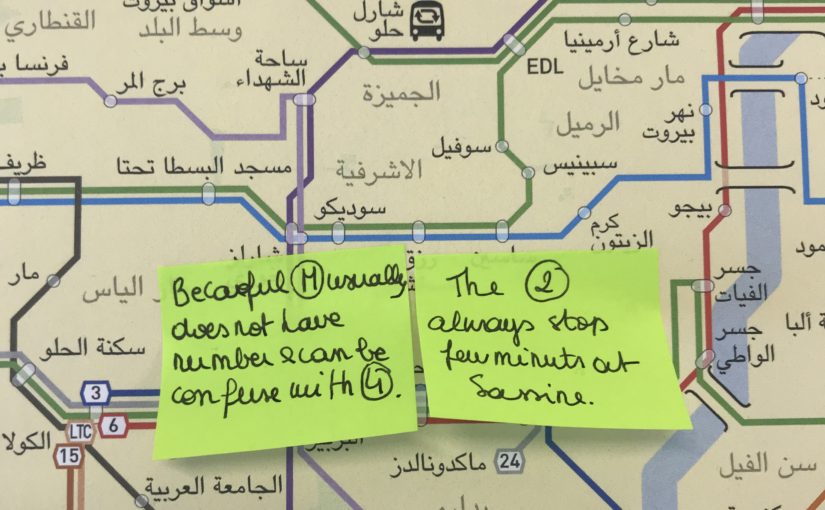

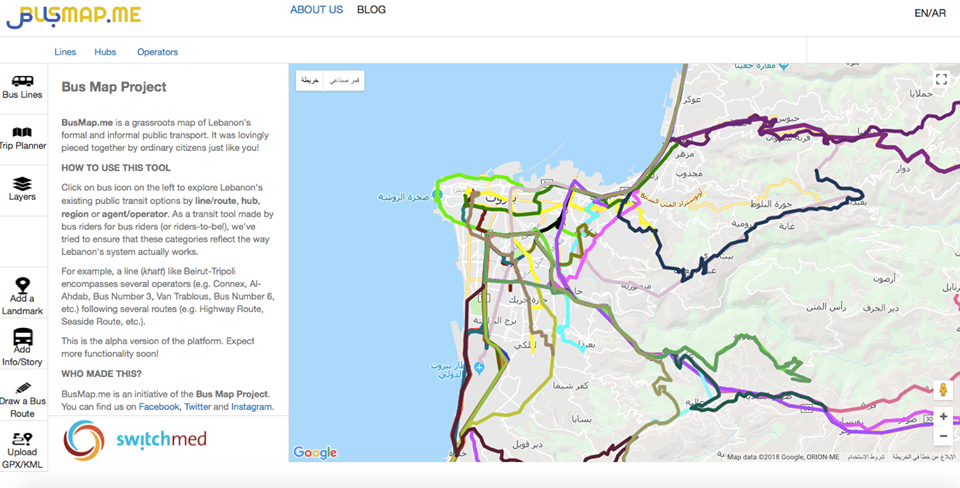

And yet, listening to MaaS being presented as a revolutionary concept sounded slightly odd to our ears. Indeed, the characteristics of these demand-responsive services are not that dissimilar to what characterizes informal transportation in our countries. Isn’t a service-taxi in Beirut “demand-responsive”? And what about the “flexibility” of Van Number 4 or Bus Number 5, intelligently adapting to traffic conditions without a GPS or traffic management control center to guide them. Learning to recognize these parallels and seeing the value of these services as flexible, demand-driven and resilient not only opens our eyes to untapped assets in our cities; it also forces us to wonder why some forms of “entrepreneurship” and “creativity” are framed as such, while others are not.

“But these informal services are not adequate!” we hear you scream. Yes, they do not meet all expectations, but just like informal transportation, MaaS is not a perfectly tailored, one-size-fits-all solution either — no, it drags with it an array of negative “externalities.” For one, MaaS services are not adequate for the customer who does not have a smart phone, let alone a credit card to load on their smart app. And, being market-based and demand-driven, they are more likely to leave out geographic areas that are not profitable, widening the economic and social gaps already striated by available (formal and informal) infrastructure. These issues will plague any unregulated service provision, but only some of these unruly operators are treated as worthy of reaching out to and bringing together, for the good of all. As the proverb goes (ناس بسمنة وناس بزيت), this is a very obvious ghee (samna) versus oil situation.

It should also be noted that in many cities across the world, there is a huge debate around the dismal working conditions of ride-hailing app “employees” — and even this word is contested — coining a new expression to describe a huge aspect of this innovation: the “uberization of work.” This problem is somewhat similar to the poor living conditions of bus and van drivers who run informal routes, who often work off the clock and in too many cases, are exploited by route- or fleet-owners. These parallels are not perfectly isomorphic, but the similarities should open our eyes to the way our public authorities can overlook the negative externalities of some operators when they’re backed by venture capital, but will not extend support to operators who may more directly benefit from partnerships. In any case, formalization must contend with these inequalities if we are to take our first crucial steps towards more cohesive, integrated, sustainable and just mobilities in our cities.

III. The Trap of Blind Formalization

As we wrote above, the true milestone set by this year’s UITP MENA Transport Congress was how informality was ‘invited in’ as a matter of thoughtful concern. This happened through two sessions: one on “Mapping and Understanding Paratransit/Hybrid/Informal Transport in MENA cities” featuring our friends from Transport for Cairo (Egypt), Ma’an Nasel (Jordan) and WhereIsMyTransport (South Africa), whom we’ve known for a long time but first met in person last October. These initiatives are doing a lot to make informal transport more legible in their respective cities, with a big focus on “big data.” We then participated with them in the inaugural UITP Working Group on Informal Transportation meeting, which took place after the official end of the Congress.

During the second session, there was a strong push from some friends in favor of dropping the term “informal” and replacing it with “paratransit,” as a less pejorative expression. While we welcome any language that shifts us away from stigmatizing views of informality, we do wonder if the “para-” in the neologism ends up re-inscribing the moral centrality of the formal in a different, though less aggressive way. Indeed, in countries like Lebanon or Turkey, where informal transportation accounts for 93.8% of transit, the word “paratransit” just sounds disingenuous. Para- to what, exactly? How can the majority sector be the marginal population?

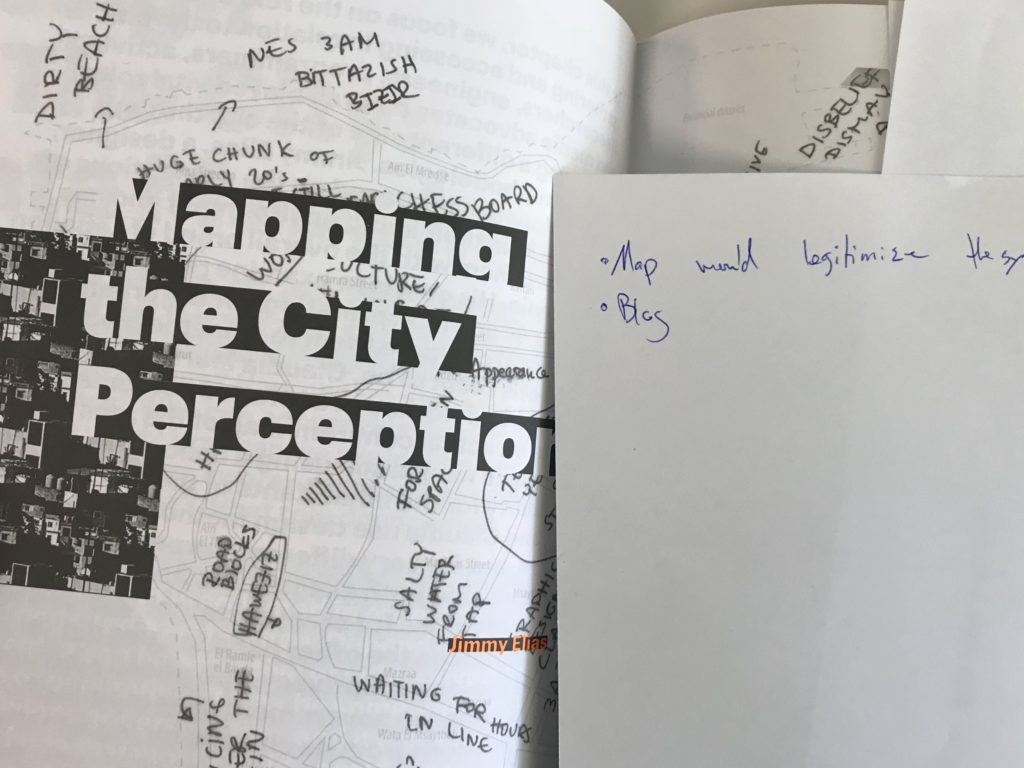

This is a healthy debate. That engineers are open to debating semantics is an ironic surprise for us, as we have heard some in similar positions dismiss civil society campaigns on the topic of the urban as “all talk.” So we can argue for and against each term, and have since submitted some feedback on the vision and aims of the Working Group upon the organizer’s request. Yet, we want to end this post by cutting to the chase. Do we want to cosmetically re-brand the informal sector, or do we dare strike at the root of this whole debate: that informality is only a problem needing a top-down fix if we insist that cities are purely managerial objects most perfectly understood by technocrats; that people who live and make a living in cities are merely prisoners among shadows, limited by their simple lives and only ever apprehending approximations of the urban systems that engulf them; that planners and regulators and engineers have the absolute and final say over what goes on in our cities; that their expertise shields them from the democratic requirements that all other social actors are expected to submit to in plural societies–persuading the public, working with others, accepting compromise and actually innovating (generating the new in the here and now), as opposed to copy-pasting boilerplate solutions proven to turn a profit elsewhere?

These are the unspoken fantasies that underlie the politics of urban (in)formality. The basic human right of free and unencumbered movement from Point A to Point B is championed by all, and then squashed by the assumption that such freedoms are ultimately in service of the much larger and more important processes of governance, accumulation, and circulation. These are ingrained as ends in themselves, the only ends, perhaps. We denizens of cities are permitted to be mobile because we are the grease in these socioeconomic wheels. Our very existence in cities, it turns out, is a benevolent concession…

We are putting things very provocatively on purpose and for a reason, because it’s time for civil society actors involved in urban innovation and advocacy to decide on the point of their initiatives: is it to simply lubricate the policy machine? Or is it to challenge it, influence it, and maybe even disrupt it?

We are perfectly capable of being reasonable. We recognize that informal systems have dramatic shortcomings and externalities that need to be addressed, as pointed out by Kaan Yildizgoz, training director at UITP: problems such as the deterioration of networks, with routes emerging to pick up the most passengers, creating highly inefficient trips and poor working conditions of transit drivers, who are often under immense pressures from their higher-ups, etc.

And yet, formalizing the system without challenging our assumptions about the role of the state and the planner and the engineer would be an even more destructive move. It is also very likely to fail, because informality stems from endogenous characteristics of the state itself, such as unfair legislation, lack of enforcement and high rates of unemployment. To solve these “externalities,” we must first put them at the center. They are rather the “internalities” at the root of the processes that generate our discomforts about service adequacy. Formalizing the informal must be inclusive and fair. This can only be done through a comprehensive framework of social and modal integration that is rights-based, not concessions-based, and led by a genuine desire to leverage the skills and expert knowledges of planners and engineers for the good of all. Let’s lead the transition.

Banner image taken from UITP Facebook Page. All rights reserved.