by Mira Tfaily

Last week, five of us from the Bus Map Project team (Chadi, Jad, Mira, Haifa and Sergej) had the pleasure of participating in a Regional Exchange conference organized by FES Cairo and A2K4D around the question of transit and mobility in the MENA region. The conference brought together grassroots mapping initiatives and various stakeholders from the engineering, advocacy and research worlds from the MENA and beyond, to spark conversations, explore synergies, and engage in new creative thinking about how to work with the infrastructures and ‘infostructures‘ we find ourselves in. Though we had different perspectives and experiences, our shared aim was “making a shift from car-oriented cities to people-oriented cities” across the region. In this post, Mira reflects on some of the interesting points of convergence and tension that came up during the conference:

“A developed city is not where the poor have cars, it is where the rich use public transportation” — these words by Gustavo Petro opened the conference hosted by the American University in Cairo, in the iconic Oriental Hall of the historic Tahrir Square campus. The two days of discussion linked up stakeholders across the pro-transit spectrum. Panels included Dr Ayman Smadi, former Director of Traffic and Transport at the Greater Amman Municipality and current Director of the MENA branch of the UITP, and five transit mapping initiatives, big and small: Transport for Cairo, (Egypt) Ma’an Nassel (Jordan), Digital Matatus (Kenya), WhereIsMyTransport (South Africa/UK), and of course, our humble Bus Map Project representing Lebanon.

Much to our enthusiasm, actors from such different perspectives seemed to have reached very similar conclusions: to tackle mobility issues in cities where there are large gaps in transit provision, the most effective way for encouraging new patterns is to rethink our old, top-down planning tropes.

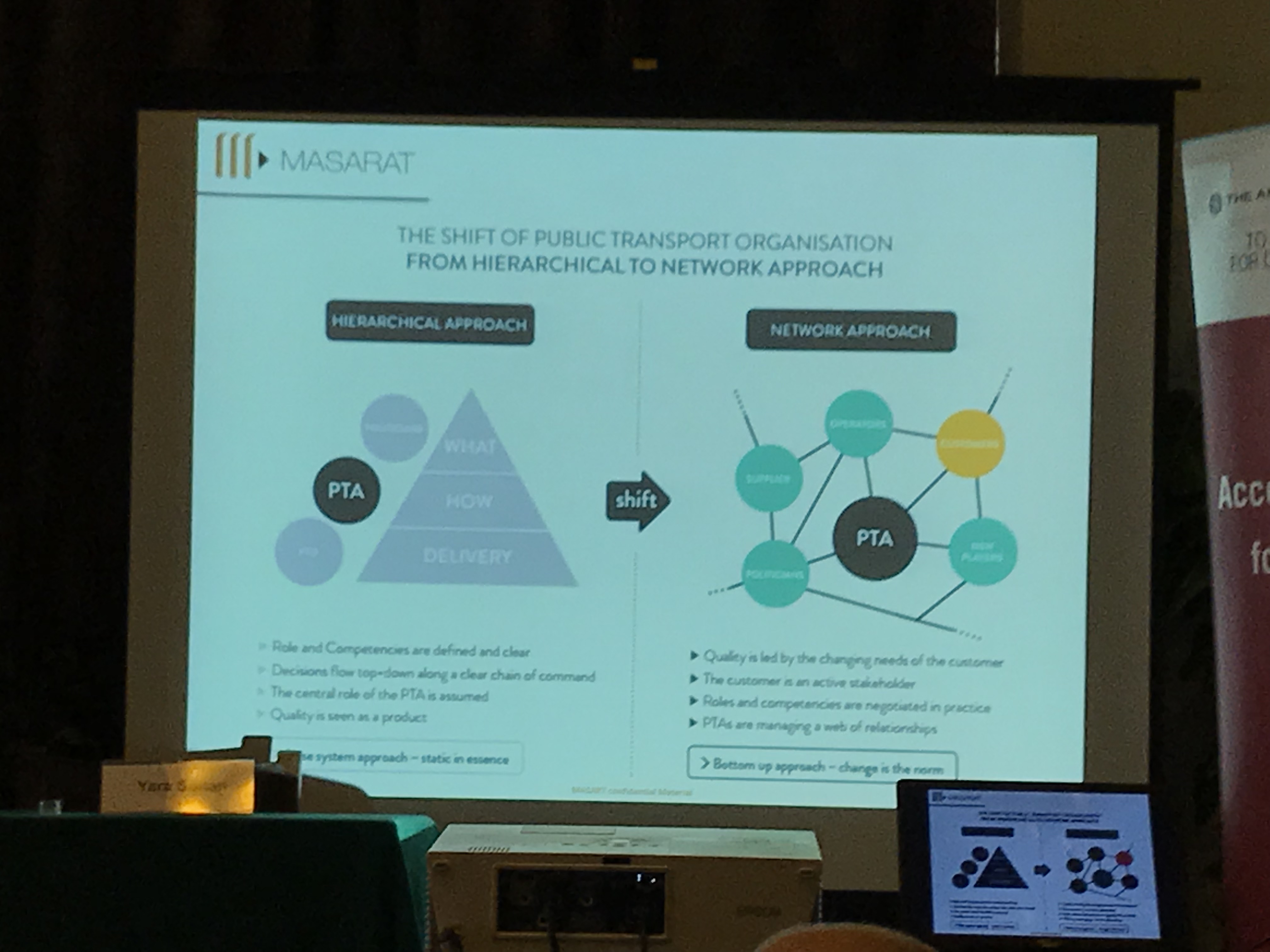

As Dr Ahmed Mosa from MASARAT put it, a crucial shift is needed in public transport organization from a hierarchical to a network approach. This surprising language from an engineer and planner helped us see that there are openings for grassroots mapping initiatives like ours to enter the policymaking conversation. Our bus riders’ perspective becomes a policy instrument and a way to give birth not only to technical solutions but to deeply sustainable ones, rooted in incremental change and the gradual adoption of new behaviors.

As the subject of informality came up again and again, we were encouraged to challenge more and more the categories and frames that shaped what we believe to be true regarding our transit systems. Dr Jacqueline Klopp from the Center for Sustainable Urban Development at Columbia University questioned the terminology used to describe the transit gap-filler: is it even relevant to call these buses and vans informal, when they are so ubiquitous and deeply embedded in society? And why is “elite-informality” tolerated, while the mobility practices of the poor are completely unacceptable? Mohamed Hegazy from Transport from Cairo suggested a more neutral term for informal transport — “paratransit” — but the question remains: what is at stake in holding on to language that neatly differentiates between centrally-regulated state-owned mass transit and privately-operated public transport?

We have always referred to the buses and vans we use and map in Beirut as “existing transit” for this very reason, and are happy to see more questions being raised about the categories we’ve inherited for understanding our cities.

The obvious nature of “data” itself was also challenged and questioned. As Dr Sarah Williams from the Civic Design Data Lab at MIT pointed out, data is only useful when it is built into a tool that benefits the public. So how can we use the data collected to highlight inequality in access and service provision? Visualizing data through a map is a powerful way to stir up and steer the conversation about accessibility, for example, but are there other ways to turn data into useful information? This is a question also raised by Bianca Ryseck from WhereIsMyTransport, who said that, as an urban sociologist, developer-focused platforms aren’t always useful for her. While many stakeholders are interested in transit data to make smart planning decisions, it is important to remember that, as Jad put it, data is “a bridge but not an end goal.”

This is why, for our project, the way we do data collection is just as important as what we do with it.

If, following Chadi’s words, transport is mirroring our society, then as citizens, we have the direct power to implement change by shifting our behaviors. What are our rights and duties regarding mobility in our cities? Isn’t the least we can do to engage with the existing system to try and understand it better? We often quote Wim Wender in our presentations, so here’s another point to consider from a cinematic auteur: “Confidence is what you have before you understand the problem,” says Woody Allen — hence, unlearning our pre-conceived ideas about mobility will eventually help us realize that maybe, just maybe, our transit problems don’t lie where we think they do. We need to rethink our questions so we can work on answering them step by step, with more efficiency and more inclusiveness.

[editorial work and input by Jad Baaklini]

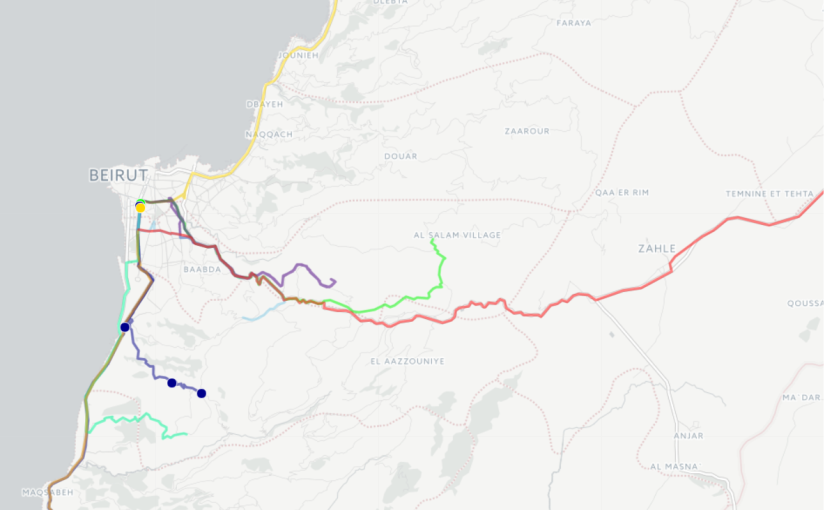

![Cola to Chouiefat [Sara and Sirene]](http://blog.busmap.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/SaraSireneMap.png)

![Cola to Baakline [Rachad]](http://blog.busmap.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/RachadMap.png)

![Cola to Aramoun/Qabr Chamoun [Ali]](http://blog.busmap.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/AliMap.png)