Today’s #HerBus post is a photo-essay by Lucia Czernin, a writer and photographer who took part in our Bus Map Photo Action last summer. We are very happy to publish this beautiful account of her thoughts and experiences exploring our first edition bus map and getting to know some of the stories — just 14 glimpses — behind that intricate human tapestry that is the riding public.

* * *

‘Who is Who on the Bus?’

by Lucia Czernin

Who are the people in the anonymous crowd of commuters? What are the stories behind them? I sometimes wonder why we are not constantly amazed to see new faces, given the fact that every face is unique in its way and represents a unique person and story. It might be a natural mechanism in order to protect us from the exhausting idea of endless new information. I guess humans need this security: familiarities, being surrounded by things and people they know, at least from time to time. In order to not lose control, we tend to divide the world into two broad categories: people we know and people we don’t know. But then, the process of a stranger changing categories, turning into someone we know, can consist of only a look, a smile, an insult or a simple gesture. This happens by chance or it can be deliberately provoked. But the idea of taking the initiative might frighten most of us, and I know it totally went against my own inclinations. And yet, as they say, “who dares, wins”.

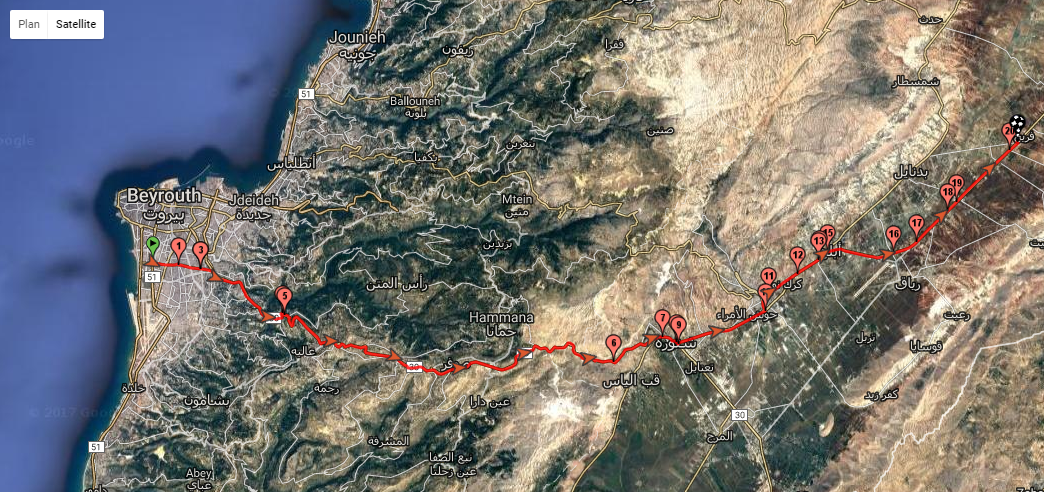

Once on board, wavering down the “autostrade”, surrounded by honking, shouting and Arabic music, I thought I actually had a very important book to read and I might not really want to get to know these people. But then, I pulled myself together and dared to stumble over some awkward question in broken Arabic to the person in the seat in front of me. Suddenly, it seemed the music would stop, and people would interrupt their shouting and honking to fix their eyes on me, asking: “What is your problem?” Humans are an amusing species: on one hand we can only survive in community, while on the other hand, we love to lead a bubbled-up life. This tendency might be particularly strong in cities and is also referred to as “civil inattention”. Especially in cities that hold twice as many cars as persons, it seems that even on the bus, people like to pretend that they are on their own. Best strategy? Catch their attention.

Usually it is not very comfortable to look like a foreigner, but in these journeys that I documented, it helped to attract the curiosity of my fellow passengers. In some instances, I was lucky to meet new friends without having to take the first step, and could very naturally engage in conversation and photograph them. On two occasions I managed to bring an accomplice along, as my moral support; a partner in crime makes you feel bulletproof! So eventually I found myself bouncing across the bus talking to strangers. And every face I captured with my camera represents a precious add-on to my personal universe:

Please say hello to Omar and Shanti. They have just gotten married, and they are perfectly happy using the bus on their honeymoon. You would think, they couldn’t be better off on a luxury cruise!

As she enters the bus, the sweet elderly lady with the “Alice” band and the matching polka-dotted cotton dress radiates an air of confidence. She is one of those people that remind you of the caring granny from your childhood. As soon as she is seated, she produces her rosary booklet out of her handbag. Although she is fully focused on her pious activity, she doesn’t mind being interrupted. On the contrary! She is delighted to explain the different parts and prayers of the rosary, indicating pages and pictures. The rosary lady of Hamra seems to be in high spirits as she goes on to explain the Novena to Saint Rita (a nun from Italy of high popularity in Lebanon). She is about to offer me her dear devotional manuals, as if it were a precious gem. Her recommendations include novenas, a prayer repeated during nine days for a special intention. In her case, it is always about health issues: spiritual and physical ones – for family members and neighbours. The photo I take is the only thing that makes her uneasy. She feels embarrassed because she hasn’t arranged herself properly this morning. But then she takes a photo of me in return, as a souvenir. And I am assured that she would always send me a prayer whenever she finds me in her photo gallery, squeezed next to Saint Charbel and company.

These two ladies have been following my conversation with the woman with the rosary, and have eagerly encouraged her to pose for my camera. Rima, the woman by the window, has been living in Lebanon for 31 years, getting married and raising her children here. We find her on her last day in Lebanon, however. Tomorrow, she will leave to her home country, Mauritius, for good. “I doubt very strongly that I will ever get the chance to come back,” she tells me. She seems to be serene about that. “What do I like about Lebanon? I love this country, especially the generosity of its people,” she says. The woman next to her, also from Mauritius, is a close friend who has been in the country for 25 years, and seems quite well established. What would be their message to the world, if they had the chance to be heard by everyone, standing on a balcony? Rima: “I will go home.”

Ahmad could have done better if he had known about the photo session on the bus. But he bears it with dignity. He came to Lebanon from Raqqa, in Syria, two years ago. Back there, he owned a Falafel place. He stuck to his domain, and is now working at Abou André. Ahmad’s family members are all in Damascus. He goes there twice a year to support them. His message to the world: “that everyone may be alright, and all may be well.”

This bright fella is on his way home from school. He lives in Basta and is in the 10th grade. School is alright, he tells me, and he particularly likes chemistry. Later he would like to become a nurse, because his cousin is a nurse and tells him that it’s a fine job. But he could also study to be a computer scientist. His message to the world: “World peace?”

This is a father of four from Sudan. He works in Achrafieh and his family lives in Dora. His children are aged 5, 3, 2 and 1, and they all go to school in Achrafieh. His job is not what he had dreamed of, but at least he can work.

Aida is going up to a village above Broumana, to her sister’s house, as she does every Sunday. Her sister needs this support since she would be lonely otherwise. Aida’s husband joins her, every time. He has been a sacristan in a church for 20 years. Aida works at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Ministry once sent her to South Africa, three years ago, on an accounting mission. She still remembers the many aunties in the kitchen there. She is 60 years old now, and doesn’t have any children. “I have cried a thousand tears because of that. But now I am old anyway,” she confides. Everything happens for a reason. Aida is the most confidant of all her work colleagues, and of her neighbours, and of her brothers and sisters, she tells me. She takes the bus every morning from Dora to Gemmayzeh. She even knows most of the other commuters who come from Tripoli, and worries about them when she doesn’t find some of them on the bus. They always greet each other. When asked about her message if she were standing on a balcony and had the chance to speak to the whole world, she first wants to know on which floor the balcony would be! “What would I say? Bonjour! Please come in!” She then adds that she would wish the world a blessed day, in case this was happening on a feast day. “Yesterday, for example, was the feast of Saint Thekla.”

As I enter the bus in Dora, I seem to be crashing a private family scene. The driver is taking his wife and son out on a Sunday trip to Jbeil. All three of them are enjoying themselves, giggling and talking loudly. The driver’s son, Ryan, is proud to be helping out his father by collecting the transport fees from passengers, as they get off at their destinations. He turns out to be quite firm, to the extent that his father has to calm him down when two ladies get away with paying only 1000 LBP each, instead of the customary 1500 LBP. I am not surprised that Ryan wants to be a soldier when he grows up. He will definitely do his job dutifully.

“My name is Felicidad. Like in the Spanish Christmas song: Feliz navidad, feliz navidad…” she sings to me. Felicidad is married to a Lebanese man. Her husband is 92 years old, she herself 45. She has children and grand-children in the Philippines. She’s never met her grand-children. She used to work as a cosmetician, but now there is no time for that, since she is taking care of her husband. A good man, she tells me. She brought along her friend Mary, who has just arrived from the Philippines. Mary needs help getting around and building up her social network.

Michelle feels great. She is on her way to work in Antelias. “If I was the owner of this bus, the first thing I would do is change the seats. And then I would remove the Smurf from the windscreen.” When asked about Lebanon, she assures that there are many positive sides to the place. To state just a few: its smallness – you will always find someone you know ore are related to. You will never be completely lost; the weather – so much sun and still you have four seasons!; the food… “Badkon chocolat?” is her message to the world.

Dunia is a refugee from Iraq. She came to Lebanon one month ago, together with her husband, her two children and her parents. She is now expecting her third baby. What she likes about Lebanon: they are safe here. They live in Jounieh and they haven’t made a lot of friends yet. There is hardly any interaction among neighbours here, she says. Her message to the world: “kounou bi aman w salam.”

Khaled is from Akkar. To him, Lebanon’s flora is a big plus, but his family always comes first. Khaled has always striven to work in the lighting sector. But after school, he started at Hawa Chicken and is now a security guard at the Canadian Embassy and at the German School in Jounieh. Through this job he has become a good observer, he tells me. But whenever he can, he gets away to Akkar. By bus, of course.

Let me introduce you to the “mas2oul” of the Crusader fortress in Byblos. This excellent man has been a loyal bus commuter from Jounieh to Byblos for 50 years. He always brings his lunch box in a small hand bag. He loves his job, since it allows him to meet people from all over the world, though he can hardly communicate with most of them, not being a fan of foreign languages. But he knows every historic detail relating to the fortress! Just ask.

This is Ahlam on her way to Zalka. She works in a spa. Her favourite part of Lebanon is her family. The only thing she really can’t stand are the slow bus drivers. She tries to avoid them. Her phrase to the world: “respect one another.”

* * *

Lucia’s story is part of an ongoing series highlighting the unique and complex experiences of women who use public transport in Lebanon. Do you have a story you want to share? We will post it with as much, or as little, editorial input as you request, to make sure that your voice is in the forefront. You can write in English, Arabic or French, and when appropriate, we will share a translation that sticks as closely as possible to the spirit of your story. Share an experience, keep it personal, make it academic, be creative — your city needs your voice!