في 10-04-2017 تمت الجلسة التشاورية الخامسة في مبنى بلدية بيروت الطابق الثاني بدعوة من شركة الارض للتنمية المتطورة للموارد ش .م.ل المسؤولة عن اجراء دارسة الاثر البيئي والاجتماعي لمشروع الباص السريع بين طبرجا و بيروت لصالح مجلس الانماء والاعمار

وكان الحضور بين حوالي 10 اشخاص جميعا مع المنظمين الذين يشكلون حوالي 4 اشخاص قد جلسنا في على طاولة مستطيلة وقد جلس بالصدفة السيدات الى جهة والرجال في الجهة المقابلة

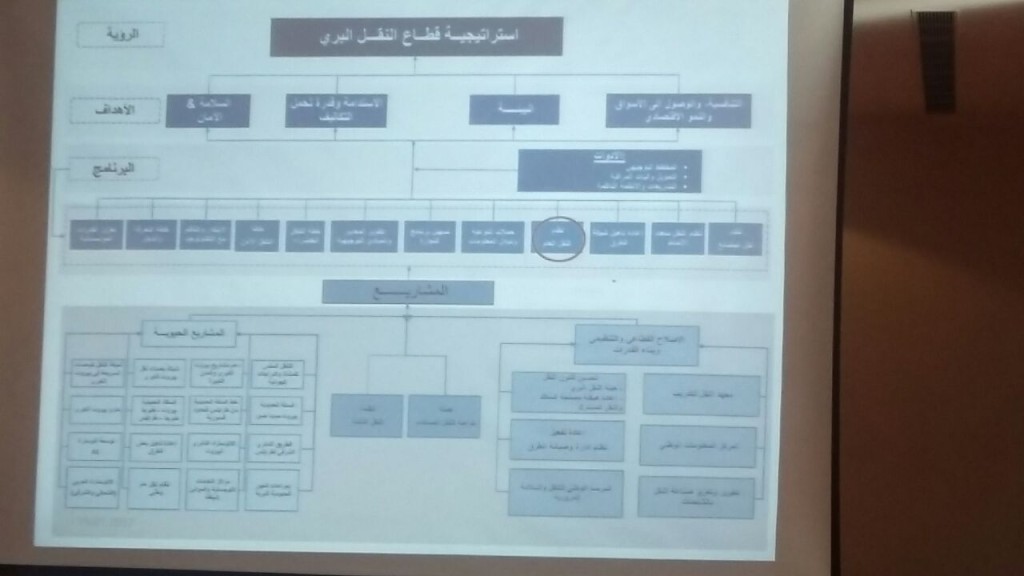

كما العادة بدأت هنادي المسؤولة عن الاجتماع بتعريف المشروع الباص السريع ومكوناته الاساسية. فتبدأ بالمقدمة عن استراتجية قطاع النقل في لبنان واين المشروع من هذه الاستراتجية. في المدى القريب والمتوسط سيكون هناك خطة نقل مرتكزة على الباصات اما على المدى المتوسط والبعيد سيكون هناك قطار وبعدها تبدأ بشرح عن المشروع بقصة نجاحه في بعض دول العالم كالمكسيك و ايران وتركيا وبعدها تصل الى وصفه بشكل عام

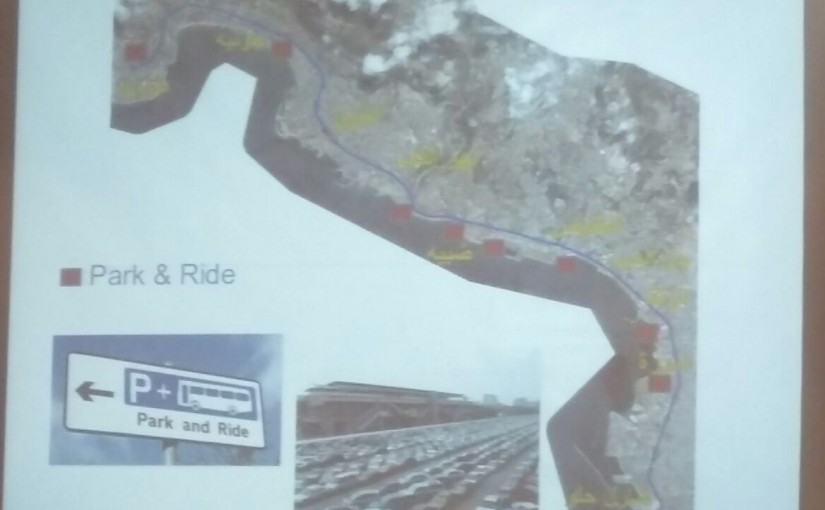

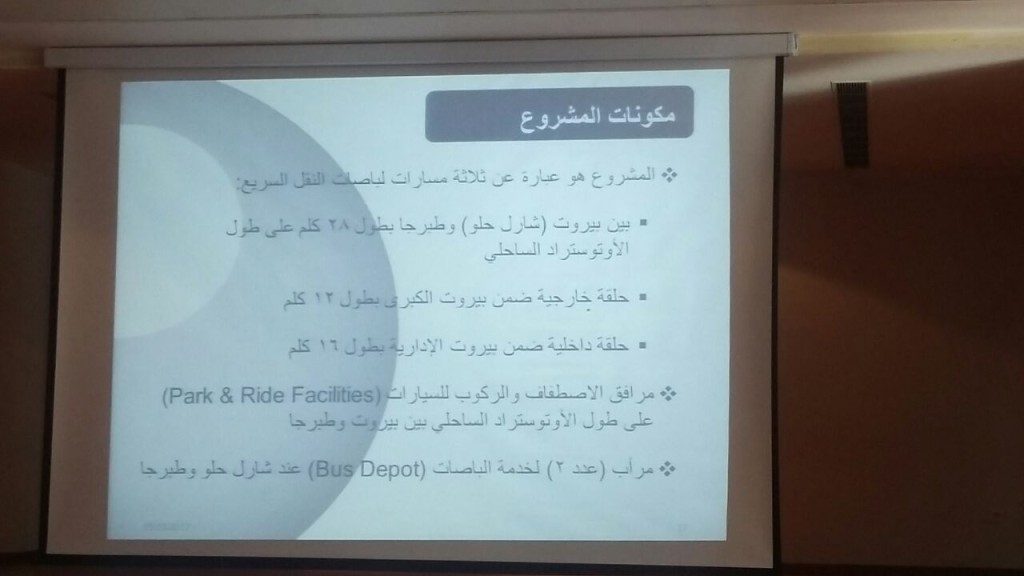

:بتألف من باص السريع من 3 خطوط

الخط الاول على بين طبرجا وشارل حلو بطول 28 كلم وسيكون في وسط اتوستراد جونيه

الخط الخارجي لبيروت وسيكون حول بيروت الكبرى بطول 12 كلم والارجح سيكون مسارالباص على الخط اليمين من الطريق

الخط الداخلي سيكون على 16 كلم ولم تحسم اذ سيكون لديه خط خاص او لا والامر متروك للدراسات الفنية

وكانت احدى اولى الاسئلة لبدء النقاش من قبل مديرة الحوار والسيدة امل التي تدير هذه الدراسة التقنية: “قديش رح يجذب هيدا المشروع ناس تستعملوا؟” … “كيف تجربتكم بالتنقل بلبنان واذا بتستعملوا الباصات”؟

وهل هناك موقف لتصف سيارتها و (feeder buses) وتكلمت احدى الفتيات وبدأت بسؤال عن الباصات المساعدة

خصوصا ان 5 كلم المسافة من الموقف الى بيروت فالافضل ان اكمل بسيارتي – “ما بقى تحرز” استعمل الباص

هنا تكلمت فتاة اخرى تقول انها تسكن في وطى المسيطبة وهي طالبة جامعية وهي تستقل الباص وفي نفس الوقت تمتلك سيارة ولكنها تستعمل الباص بسبب زحمة السير

وبعدها تناوبت على الكلام طالبة جامعية تتعلم في الجامعة اللبنانية في الفنار وهي تذهب الى الجامعة بالباص فتستعمل باص رقم 15 من الكولا الى الدورة ثم الباص من الدورة الى الفنار رقم 5 ولديها مشكلة مع الباصات الحالية “النطرة” التوقيت دائما ما نصل متأخرينا “عطول بدنا ننطر كتير او منوصل مأخرين” وقد اعطت رأيها انه يمكن في بدأ الامر يكون رفض للمشروع ولكن مع الوقت الناس ستستعمله

وقد عانت احدى اصدقائها بأحد الخطوط انها كانت تبكر في النزول لانتظار الباص قبل اكثر من ساعة لان لا جدول محدد وكانت مشكلتها في العودة الى البيت في الليل حيث انها لا تدري ان مر اخر باص او لا تحتار في الانتظار اكثر او ماذا تفعل وخصوصا ان كلفة النقل ستكون اعلى عليها وهي تريد ان توفر المصروف قدر المستطاع

هنا انتقل الحديث الى احد الشبان وقد عرف عن نفسه انه دكتور وكان يعيش خارج البلاد وانه يستعمل النقل المشترك كثيرا وخصوصا في اوروبا وانه لم ولن يستعمل غير سيارته في بيروت وذلك لسبب مهم في نظره وهي النظافة فهو طبيب ولديه عيادة على الكورنيش وكلما مر من جانب الفانات والباصات فتصل اليه الرائحة والدخان المبعث من الفانات والباصات

ويصف الباصات بالغير دقيقة المواعيد ويجب ان يكون لديها قدرة على استيعاب ساعات الذروة ويسأل كيف يمكننا اقناع اللبناني بأستعمال الباص وخصوصا ان اللبناني لديه الميل والطلب ان يصل بوسيلة النقل الى امام المنزل وهو يتذكر باصات الدولة في ال90 حيث كانت تسمى “جحش الدولة” والتي كانت تقفل الطريق بحجمها فطالب ان تتناسب الباصات بحجم الطرقات الصغيرة وخاصة في احياء بيروت

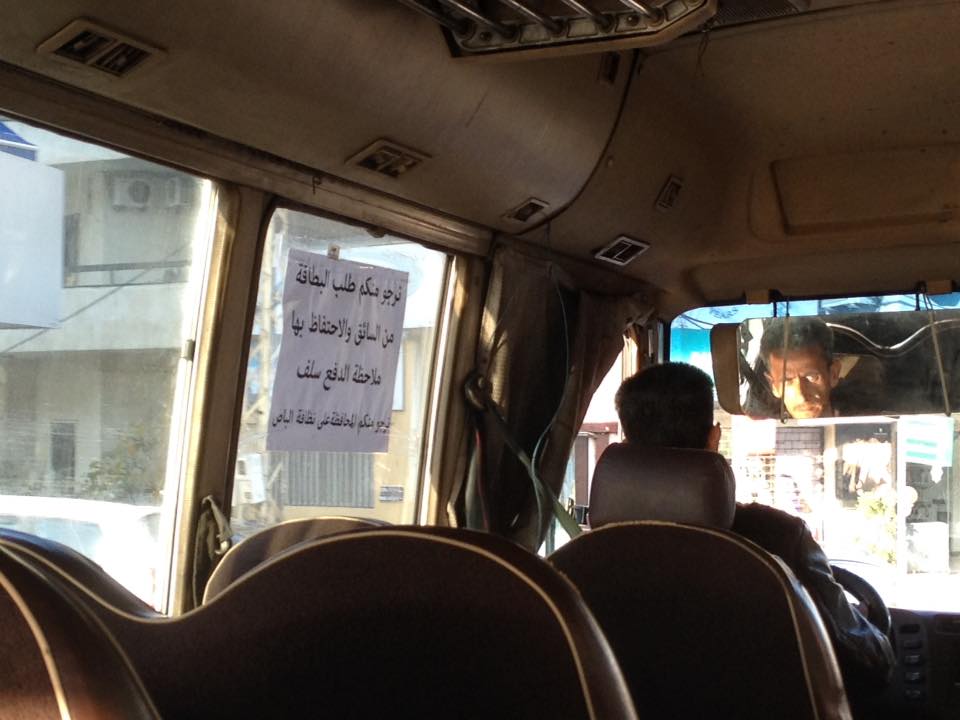

كما طالب بتعليق المعلومات باللغة العربية والقيام بحملات دعائية للباص واكد ان اللبناني يريد محافزات كبيرة ليترك السيارة وتفعيل قانون السير والاشارة والخطوط car pooling الخاصة واطلب بنشر فكرة الاستعمال المشترك للسيارات

وطالبت احدى الفتيات بالسلامة المرورية وخاصة للام التي تجر عربة الاطفال وتريد الصعود على الباص الان فيجب تحسين النبى التحتية الان

وقالت انها ليس لديها اي خبرة في الباصات الا في باص بيروت صيدا landscape architect استلمت الكلام

وذلك لانها تخاف السرعة وخاصة في الباصات والفانات الصغيرة حيث السائق يسوق بسرعة جنونية وان باص صيدا بيروت هو خط مقبول وله توقيت محدد وفعال وهو لشركة خاصة وان الدولة عملت على الخطوط نقل الباصات وقد فشلت وان من اسباب ذلك اسباب سياسية وخاصة ان هناك بعض الخطوط وقد اخبرتنا انها تخاف الصعود ببعض الباصات خاصة انها قد يأتي احد ويقطع الباص خط الباص الذي تركبه وذلك لسيطرة بعض الاحزاب السياسية عليه وقد نصحة انه اذ لم يكن من استراتجية لادخال المستفدين من القطاع الان ذلك سيشكل سبب في فشل هذا المشروع وتسألت كيف يكمن ان يتكامل هذا المشروع مع السرفيس هل هناك مواقف للسرفيس بجانب خطوط الباصات

وبدأ بتحليل المعوقات لتطوير العمل في المشروع فقال يجب معرفة اللاعبين الاساسيين architectبعدها اخذ الكلام

اولا السياسيين والسياسة ثانيا البلديات وثالثاً اصحاب الخطوط وهم المتضررين الاساسيين ويجب ايجاد طريقة لادخالهم في النظام الجديد وانه يستعمل الباص وخاصة فان رقم 4 وانه استعمله اليوم ولم يفكر بالتردد للحظة لانه لو اتى لم يكن سيعرف اذا هناك موقف للسيارة وكم ستكون التكلفة وخاصة ان تكلفة الفان 1000 ليرة لبنانية وقد تمشى قليل ووصل بكل سهولة الى مكان الاجتماع دون ان يتأخربغض النظر عن حالة المقاعد في الفان او الرائحة والدخان وان ليس من الغريب تحمل استخدام الباص بحالته الحالية فكلها مدة قليل للركوب والوصول الى المكان المقصود وبتكلفة زهيدة وسأل كيف نريد ان نحفز الناس ان تستخدم الباصات هل يجب زيادة كلفة المواقف هل يجب الغاء المواقف وقال الجيد انكم تستطيعون التحكم بالتوقيت الباصات لانه المسار خاص والا فأن سرعة السيارة وحتى على الاتوستراد لا تتعد 10 -20 كلم بسبب كثرة السيارات وذلك كان قد طرح مشاكل في التوقيت للباص

بعدها قد تكلم احد الاشخاص الذي كان حاضرا وهو صديق وكان من الناشطين في احد مجموعات النقل المستدام وقد تكلم عن تجربته الشخصية فبدأ حديثه انه لطالما استعمل النقل المشترك منذ كان تلميذا فقد كان يأخد من برج البراجنة الباص رقم 12 ثم بعد ذلك يتسعمل السرفيس بسبب بطىئ الباص الذي قد يصله الى المدرسة

بعد ان توظف واصبح لديه قدرة مادية ما زال يستعمل فان رقم 4 وخط الفان الشويفات وبالنسبة له ان يستعمل النقل المشترك لانه مقتنع انه مفيد البيئة ولا يستعمل السيارة الخاصة الا عند الحاجة او ايام عطلة الاسبوع

والان اصبح عندي تحدي اذا انني قد اخطو خطوة جديدة في حياة الشخصية واتجه نحو الارتباط فلا اعتقد انه ما زال بأمكاني استعمال الباص وخصوصا سيصبح لدي عائلة

لدي النصائح عند استعمال فان رقم 4 فبعد الساعة ال 9 لا استعمله بسبب سرعة السائقين وانا اريد ان احافظ على حياتي احب ان اقرأ في الباص وما يزعجني في الباص كثيرا هو بعض الموسيقى وخصوصا الدينية

وقد طالب بوجود بعض القواعد لركوب الباص وخاصة في ما يتعلق بالحيوانات الاليفة فهو لا يحبذ وجود قطط في الباص ويرحب بوجود كلاب

وقد قال انه ليس لديه مشكلة في اعتماد نفس النظام في دبي بخصوص التمييز بين الخدمات الملكية والخدمات العادية وهي نوع من الحل للفصل بين طباقات المجتمع وطبعا ساد نوع من النقاش الحاد بيننا ولكن في الاخير لا نعلم ماذا يمكن ان يحدث وخصوصا ان التعرفة لم تحسم بعد وان كانت التعرفة ستدرس لتناسب كل مستويات المجتمع وسكانه

وقد طالبت احدهن بتدريب السائقين على عملهم وكذلك ان يكون سائقات اناث للباص السريع

وقد شاركتنا احدى الصبايا تجربتها عن باص 15 انه بطيئ كثيرا و خصوصا في الدكوانة ويأخذ الكثير من الوقت ويقف كثيراً وبعدها يصل الى عجقة السير فتكون النطرة نطرات والسائقين يتسلون كثيرا من الوقت على الهاتف وهذا خطير على سلامة الركاب فضلا انه في اغلب الاحيان يحدث نوع من السباق بين الباصات واحيانا مشاكل وهذا امر خطير جداً

وقد طرحت صبية مشكلة ستواجها وخصوصا ان الخط الباص السريع لن يصل الى طرابلس بل الى طبرجا فهي كطالبة تأخد اغراضها و تكون احيانا كثيرة وهي لن تقوم بأخد الباص اذا لم يكتمل الخط فأما سـتأخذ خط اخر متل الكونكس او سيارتها لان ذلك سيمنعها من التعب والبهدلة في حمل و نقل الاغراض

وهناك فتاة قالت انها تستعمل الدراجة الهوائية والسرفيسات وتذهب بالبسيكلات الى اكثر الاماكن وهي قد اعتادت الامر رغم بعض الخطورة وقد هنأئها الحضور على ذلك وقالت انها ستسعمل الباص اذا كان باص موجود وتترك الدراجة وطالبت اذا بأمكانها اخذ الدراجة في الباص حيث انها تكمل رحلتها بالدراجة بعد استخدام الباص

وطالبت بأنشاء مسار خاص للدراجات موازي لخط الباص وذلك بعد طرح الفكرة من اكثر من شخص وصفت نفسها انها شخص يمشي كثيرا وانها تحب المشي ولكن ليس هناك ارصفة وهناك الكثير من التعاديات على الارصفة

او تقسيم التسعيرة على pay as you go وعندما بدأ الحديث عن السعر احدهم تحدث بشكل عام عن طريقة الدفع

تقسيم المناطق وان يكون هناك بطاقة ليوم كامل وان يكون هناك بطاقات خاصة لكبار السن والتلاميذ

وسأل احدهم هل هو نقل عام او مشترك لنفكر بالسعر وخاصة انه يدفع 1000 ليرة ولا يمانع اين يجلس المهم ان يصل بالنسبة للخدماتinclusive فالسعر مرتبط بالخدمات وعن مدى ارتباط السعر بمن نريد ان يستعمل الباص فكم نريده ان

وقد اردف انه اذ فقط يجب ان نحسب الامور على مصاريف النقل يمكن ان يجد المواطن حلول كأستعمال السيارات الصغيرة التي قد تكون اوفر له من الباص

وقد طرحت احدى الصبايا ان لا مشلكة لديها ان يكون الشوفير غير لبناني كذلك وانها لن تدفع اكثر مما هي تدفع الان للسرفيس 2000 ليرة فهي لن تدفع اكثر للباص

وان مصروف احد الصبايا 6000 ليرة يوميا بأستعمال الباص ذهابا و ايابا من قرنة شهوان الى انطلياس

وان كلفة باص صيدا 2500 ليرة وهو سريع و فعال ولديه خدمة جيدة وفي بيروت تستعمل السرفيس وهي قد تخلت عن استعمال الباص واصبحت تستعمل سياراتها بسبب الزحمة لمحاولة الوصول الى عملها على الترم

وقد اطلعنا احدهم على فكرة لم نسمع بها قبل ان هناك دراسة للنقل في اتحاد بلديات الضاحية الجنوبية قد تدمج رقم 4 في الخطة فلا بد من التحدث الى البلديات وان تكون جزء من هذا المشروع وسأل كم بلدية وافقت على هذا المشروع على طول الخط

رغم اننا لم يعطنا دور الا في النهاية لنقاش بناء على طلب مديرة الجلسة عدم المشاركة الا اننا كجمعيات وناشطين تكلمنا في اخر الجلسة واعطينا وجهة نظرنا عن المشروع بشكل عام واننا لا نريد ان نحمل المشروع كل مسؤولية وافكارنا ولكن لا بد من التفكير في هذا المشروع كجزء من التنقل في المدينة فيجب ربطه مع المساحات العامة والتخطيط المدني للمدينة والعمل مع جميع المساهمين في القطاع و محاولة اشراكهم بنظرة ايجابية عن المشروع ليكون هذا المشروع جزء من سياسة عامة واهمية تراتبية تنفيذ هذا المشروع فقد تكون نقطة كبيرة في فاشله اذ لم ندرس من اين نبدأ التنفيذ

ان الافكار التي تطرح في هذه الاجتماعات نرجو ان تلاقي اذان صاغية و خصوصا اننا نريد انجاح هذا المشروع ليكون الخطوة الاولى في اعادة سير قطاع النقل العام و المشترك في لبنان وخصوصا ان الكثير من هذه الاراء كنا قد طرحناها سابقاً ولان تطرح من عدة اشخاص ومستخدمي الباصات فلا بد من العمل على ادراجها في التخطيط لهذا مشروع لضمان نجاحه