This is a follow-up to the previous post, titled ‘BRT & Inclusion’.

As you can see from these slides, the BRT project consists of:

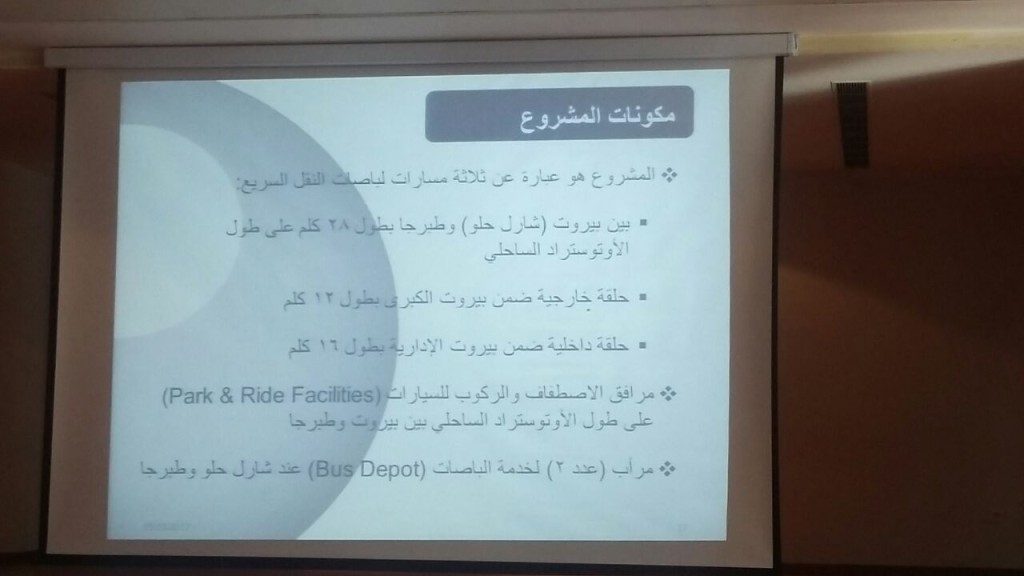

- Three BRT routes, including two loops within Beirut and its outskirts, and one northbound axis terminating in Tabarja (N.B. the bus service is supposed to keep going until Tripoli, but this would happen in mixed traffic, i.e. without a dedicated lane).

- For the northbound route, the dedicated lane will occupy the center divider of the highway, necessitating the building of pedestrian bridges connecting each side of the highway to 28 bus stations separated by 850m. The specifications of the two circular routes are still being studied, segment-by-segment, but from comments made in the Q&A session, these routes will most likely use the right side of the road (i.e. take up parking space), with around 23 stops separated by ~500m.

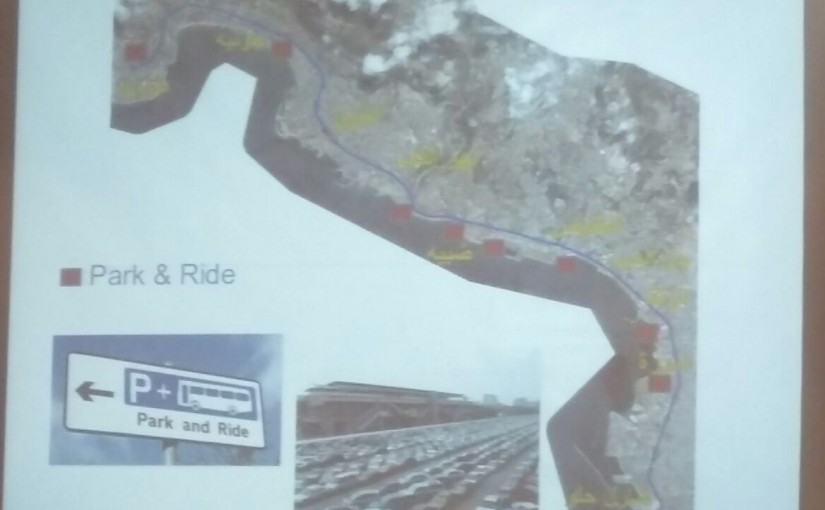

- Eight park-and-ride facilities, on land already owned by the OCFTC, in areas like Dora, Antelias, Nahr el-Kalb, etc. These would allow people to park their cars and hop on the BRT, hopefully reducing the amount of cars entering Beirut from the north.

Some experts and activists will justifiably want to follow up on every single one of these details, but we’ll keep our eyes on the bigger picture for now (but not too big; this project will certainly not solve the problem of the over-centralization of jobs and services in Beirut, as one audience member complained on Thursday):

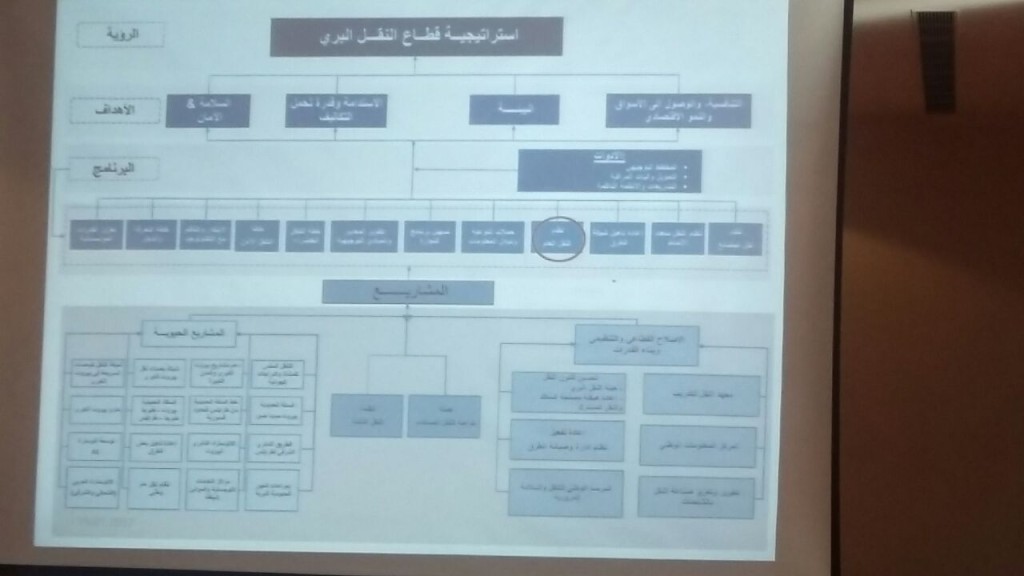

These three axes are expected to fit into the existing bus system, and to integrate additional routes that the Ministry of Public Works and Transport is also planning. The same park-and-ride facilities could potentially also be used for the revitalized railway project that is also part of the MoPTW’s master plan.

More broadly, the northern axis could — in theory — motivate the OCFTC and the private sector (and maybe even some enterprising municipalities) to invest in feeder links that connect suburban towns and villages to the coast. Clone this project in other regions, and car-dependency could drop dramatically over time. By creating new flows and interconnections, who knows — maybe even the problem of over-concentration will be lessened over time, as new markets are created in better connected regions.

By finally tackling the problem that most people complain about on the road (i.e. traffic congestion), the state would be in turn liberating the pro-transit lobby from a forced obsession with road safety and air pollution. Hence, another effect of this project could be to shift NGO priorities to more specific improvements, like advocating for rural transport, night buses, nationwide cycle infrastructure, etc. The BRT system could also draw attention to problems we all know exist, but which are kept out of sight, out of mind: if prices are affordable, there may be more mixing of social classes and nationalities in our highly-segregated city, forcing latent tensions into the open, and creating more sites of intervention for rights-based advocates.

Keeping this bigger picture in mind does not mean that we can afford to engage in fanciful, blue-sky thinking, however. The only way we can get to the bright and dynamic future described above, with all its opportunities and challenges, is to get a viable system built, and the only way to do that is to do the hard work of getting more people to talk to each other more often.

Spoiler alert: this is a political process.

At one point during Thursday’s session, a presenter assured the audience that this theoretical system-wide integration isn’t a complicated issue: “nothing is unsolvable” (ma fi shi ma byen7al), he said. This is certainly something we believe as well — if we didn’t believe that, we wouldn’t be here, doing what we’re doing. But it would be naive to think that integration would happen by itself.

Participatory systems are only as effective as their mechanisms of reconciliation — in other words, there’s no use listening to a variety of views if there’s no means of fitting them together in a coherent and broadly-satisfying way. This is especially imperative for infrastructural projects which are inherently meant to meet a wide range of needs. As we often find out too late in the game, nothing is purely technical, and all infrastructures “are inevitably imbued with biased struggles for social, economic, ecological and political power to benefit from connecting to (more or less) distant times and places” (Graham and Marvin, 2002: 11). That quote’s a mouthful, but it’s the reason why engineering can’t be simply left to the engineers.

With regards to public transport in Lebanon, we know from research that many existing stakeholders in the sector want the state to return to its role as regulator, but there is a lack of trust between them, and little confidence in the state’s ability to play this part. One researcher has described this situation in the following terms:

“Although [operators] prefer more regulation and order under transit reform on one hand, they are also apprehensive of their future roles, on the other hand. Placing blame on each other also suggests a “prisoners dilemma” scenario in which each stakeholder operates individualistically, lacking the reassurance to cooperate in a mutually beneficial system.” (Aoun, 2011: 8)

From what we heard on Thursday, it appears that the proposed BRT system has the potential for becoming a catalyst of such a “mutually beneficial system.” The design is supposed to leave enough space for other operators and modes — since there seems to be a (technical) way, all we need to wait for now is the (political) will.