As we saw in a previous post on the BRT Environmental and Social Impact Assessment study that we’ve been covering extensively, a major factor influencing the receptivity of people to the project is “perception.” Generally speaking, having more facts about the project can help bring different perspectives together, but this does not mean that all views are easily reconcilable. Everyone has their own reasons for championing one view of the sector over another, and it is easy to get frustrated with “narrow interests.” But at the end of the day, individual or group bias is the natural starting point for any conversation. We all come to a topic “from” somewhere, and we all take part “because” of something. This is half the fun of democracy, but it is also half the burden.

The same is true for public transport in general. In our last post — part of the #HerBus series we’ve just launched — we see an example of a young woman who decided to try the bus as a means of re-inventing her identity and place in Lebanon, after some time abroad. In other words, many people’s motivations for championing public transport are not primarily economic or environmental; they want comfort, peace of mind, or prefer the bus because they can daydream while watching the city scroll past their window. The bus can make poet-philosophers out of all of us, and our right to public transport, in many ways, is at its core a right to switch off and experience the life of the mind, even if fleetingly, during our daily commute.

The challenge lies in making sure our perspective — our reason to care — does not crowd out the reasons, perspectives and “cares” of others, especially those for whom public transport is a fundamental part of survival. All people are created equal, but not all stakes in the sector are the same. This is why the point of view of transport worker syndicates is absolutely vital, even if it “inconveniences” the whole project.

Here’s the second challenge: Anyone seeking to include the voices of transport workers should be really committed to this goal, and not allow the way the system has been set up to become a game they play before moving on (“we called them and they didn’t send anyone,” etc). The need to deepen relations within the sector and beyond the formal representative mechanisms is not something that will be fulfilled during any particular consultation study, but it does require sustained effort and time from a network of advocates that build real and lasting relationships inside and outside of the syndicates, that, in turn, cumulatively get us to that more ideal culture of inclusiveness inshallah. We are happy to know that ELARD agrees.

* * *

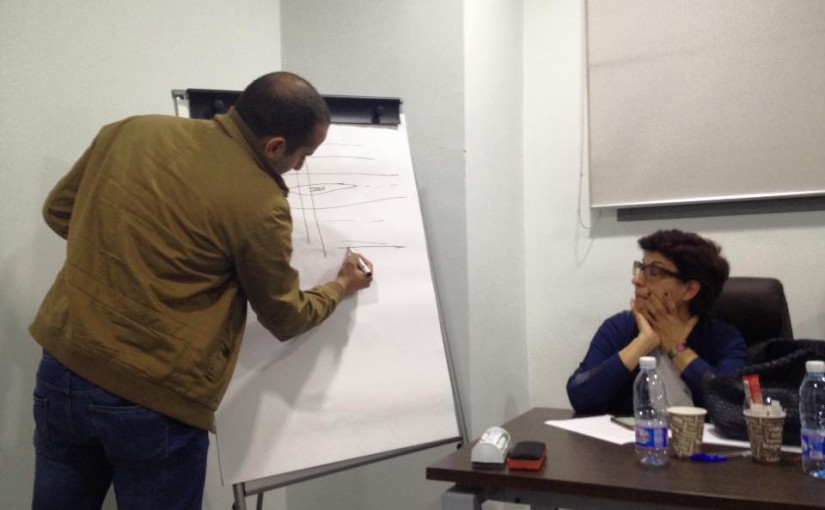

Way back on the 7th of February, ELARD opened up their consultation process by holding the first focus group meeting with transit unions at their office in Zalka-Amaret Chalhoub, near City Mall. Several transport-related unions and syndicates were invited, though only two representatives attended (for reference, a full list of unions is included at the end of the post).

We always talk about the importance of including existing transport operators in any proposed reform of the sector, but taking part in this session reminded us that it is too easy to romanticize this process, as though complex negotiations involving multiple, and often times clashing interests, with little-to-no history of interaction and commonality, can come to a quick and tidy resolution over coffee and petit four.

And yet, even with just two unions represented, a lot of useful information was shared, and through a spontaneous interplay between concerns over design and worries over jobs, the gap that can be filled today by groups seeking to reconcile divergent views became a little clearer.

To help keep our focus on this gap, we will not detail everything that was discussed in this meeting. Rather, we will try to thematize the proceedings to highlight the areas where more attention and dialogue could help bring us closer to that more ideal system of participation that we all aspire to reach:

Points of Convergence:

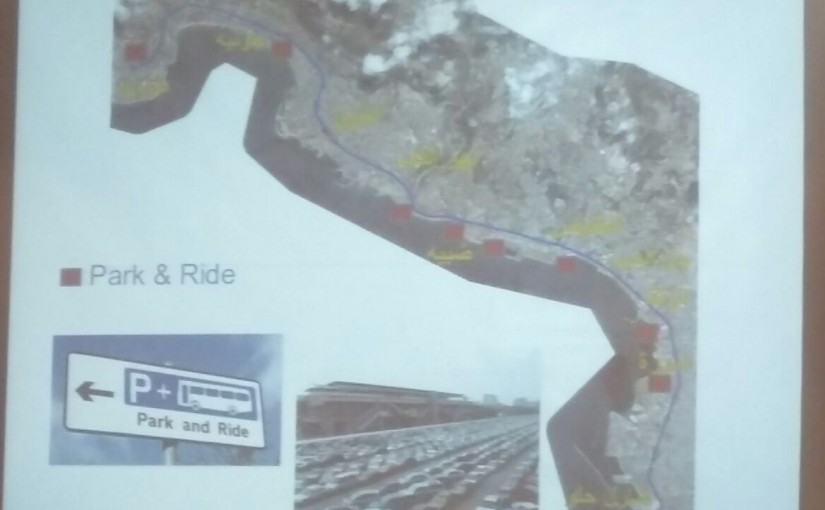

The most common theme during the session was integration, though it was not necessarily expressed that way by all sides. Elias Abou Mrad of Train/Train was very concerned about making sure that each “island” (the areas in the highway where bus stations are built) is well connected to the other sides of the highway, in a way that takes into consideration the psychology of pedestrians. He believed that the success of the project lies in how integrated the transition from one side to the other feels for bus users, and recommended that the design of each island/bridge extends past the edges of the highway, so that open spaces are found on either side. This is important to avoid the feeling of crossing a barrier which inevitably comes from any major road slicing through an urban area.

Trying to imagine the implementation of this recommendation was eye-opening for us, as it was difficult to mentally picture where these open spaces could be found without going back out and exploring the whole highway on foot; the very fact that the meeting was being held in a part of Zalka that several at the meeting indicated they had not mentally imagined as part of Zalka proper further proved Elias’ point. And though it first seemed unrealistic to find open spaces at the entrance of every single pedestrian bridge given how randomly buildings have developed alongside the northern highway, the way that this suggestion forced us to re-imagine how the urban fabric can stitch itself back around the ‘gaping wound’ of the highway was very useful for us, as pedestrians who have learned to run across barriers and make due with the car-centric urban environment. “We have to set the policy in ideal terms,” Elias insisted, “and see how much we can reach that.”

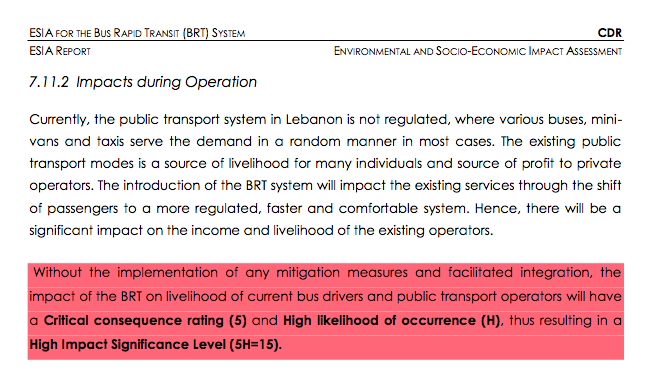

From a different perspective, “General Federation” unionist Elie Aoun insisted that the project’s success lies in the socioeconomic integration of bus and van drivers who rely on the northern highway. He explained how leaving these workers as an afterthought will cause a big shock to the system, as their livelihoods are at stake, and insisted that alternatives or incentives must be found for these workers so that they see the BRT project as a positive development, and not an antagonistic intruder. “It’s a matter of image,” he explained, as much as it is a problem of competing interests.

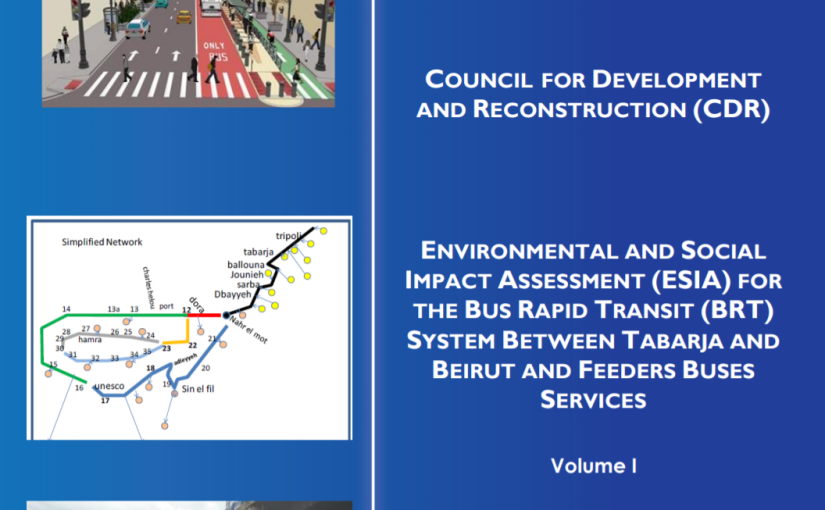

The point of convergence between these two positions — the design problem of stitching together the urban fabric, and the sociopolitical problem of avoiding friction between two transport markets — is clear, but it is not necessarily obvious, as both sides focus more on their own primary concerns. Hence, it is absolutely imperative for the CDR to take the lead here by adopting a posture of reconciliation towards both sides, and doing the meticulous work of bridging the technical (with its focus on consumers) with the social (with its focus on service providers) in a solution that is mutually-honoring. In other words, for this project to succeed, the CDR must not act like one more lobby among others, but rather, to be the forum in which diverging views are heard, understood, and satisfied.

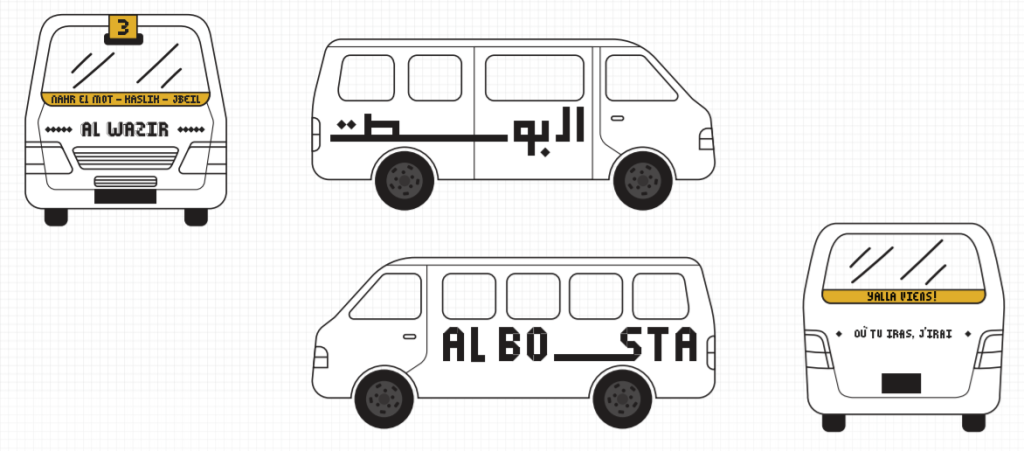

How can this be accomplished? We will not claim to be experts — especially when it comes to the granular level of every island and bridge — but, drawing on a comment that Elias Abou Mrad made, we can suggest the policy framework that ought to color every decision made in the design phase: at this stage, the average user imagined by the design cannot simply be the person who currently owns a car and is projected as likely to stop driving when the BRT system becomes successful. It cannot even be the existing bus user, who is expected to switch modes (while also being portrayed as another “problem” to solve, given their existing transit-riding habits and practices), from the informal to the formal system. Even the unions seem to agree that these transit users will make the switch, and hence, threaten the livelihoods of existing bus and van drivers. But having these two users in mind at this point skips over the fact that car drivers will only abandon the car when the BRT project is complete, and existing bus users will only make the switch when the routes they already rely on naturally and effortlessly fit into the new system. These two developments might happen rapidly, perhaps with the very first fleet to depart on day one of the BRT service; but we would like to suggest that this scenario is more likely to happen if the average user being imagined at this stage of the design phase is the existing transit operator: taxis, services, Uber, vans, buses, Bostas…

The issue of how feeder links will work cannot be an afterthought, and, indeed, this came up several times during focus group meetings with the general public over the next few weeks. It cannot be left as an emergent design shaped by market forces or other self-organizing dynamics, because there is no guarantee that these forces will go in the direction that support the BRT project (indeed, the issue of violent opposition to the project was brought up several times during the meeting). In our view, this is the most concrete bridge between Abou Mrad’s concerns about the urban tissue and Aoun’s worries over the socioeconomic fabric.

Points of Divergence:

This point of convergence, and potential site for cooperation, was undermined somewhat by subtle comments that were made that seemed to take us backwards by de-legitimizing public transport as it exists today. On the one hand, when a suggestion was made of directly compensating existing drivers who may lose business, the question was raised about “why the Lebanese people should pay for that,” as though the perfectly reasonable, free market mechanism of buy-out and buy-in was a burden too high to ask of the taxpayer. On the other hand, when the question of how passengers will deal with dedicated bus stops when they are so used to disembarking anywhere along the route, the blame was put on the transit user, as though the perfectly reasonable use of affordances provided by the system itself was a moral failing of individual riders. In both cases, the burden of change was discursively shifted in the wrong direction. When the state has been absent from a sector, it is not up to those who filled the void to somehow be less inconvenient to it when it decides to return. And when a system provides little to no structure for its users, it is not up to them on an individual basis to create that infrastructure through sheer willpower alone (though — irony of ironies — they often do).

Hence, for this process of bridging perspectives together to be truly effective, we need to once and for all exorcise that implicit but ever-present spirit of disgust that hangs over our discussions of existing public transport. We cannot reconcile differences while holding grudges. Let us, instead, accept where we are and excel within existing parameters — joud bel mawjoud.

List of Transport Syndicates invited to the Focus Group, in Arabic:

- النقابة العامة لسائقي سيارات الاجرة اللبنانيين

- اتحاد نقابات سائقي السيارات العمومية للنقل البري

- الاتحاد العام لنقابات السائقين العموميين وعمال النقل في لبنان

- الاتحاد اللبناني لنقابات سائقي السيارات العمومية ومصالح النقل في لبنان

- اتحاد الولاء لنقابات النقل والموصلات في لبنان

- نقابة اصحاب شركات ومؤسسات التاكسي في لبنان

- نقابة اصحاب الاوتوبيس والسيارات العمومية ومكاتب النقل في الجمهورية اللبنانية