The National Urban Policy (NUP) programme, initiated in 2017 by the UN-Habitat in Lebanon, aims to support the management of the country’s urbanization by evaluating ongoing practices and promoting new sustainable ones that can help improve prosperity levels, environmental quality, and quality of life. Transport was identified by the programme as one of two sectors, along with housing, particularly important for the country’s sustainable urban development.

The National Urban Policy (NUP) programme, initiated in 2017 by the UN-Habitat in Lebanon, aims to support the management of the country’s urbanization by evaluating ongoing practices and promoting new sustainable ones that can help improve prosperity levels, environmental quality, and quality of life. Transport was identified by the programme as one of two sectors, along with housing, particularly important for the country’s sustainable urban development.

In this blog, we would like to present to you a summary of the report published in 2021 by the UN-Habitat on the transport sector in Lebanon. After an overview on Lebanon’s transport sector, the guide brings up the main challenges and opportunities, alongside possible policies and future trends for the country.

The report emphasizes that Lebanon is one of the most urbanized countries in the world, with 88.5 percent of the population living in urban areas. This obviously puts great pressure on urban transport infrastructure resulting in a deterioration in the quality of services, the environment and people’s health and well-being. As the UN-Habitat points out, there is an urgent need to find new solutions for affordable, reliable and safe mobility in the country.

solutions for affordable, reliable and safe mobility in the country.

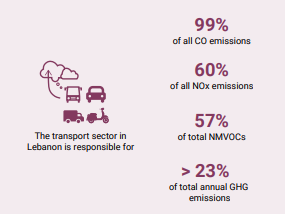

The transport sector in Lebanon is considered one of the most unsustainable in the Middle East region, due to weak governance structures and regulatory frameworks, the absence of a modern and reliable public transport system, and a culture dominated by old-model polluting cars. This situation is connected to a number of negative impacts, such as a poorly planned urban transport infrastructure, high levels of roadway congestion at all times of the day, and the environmental, health and financial cost burdens.

The transport system in Lebanon does not give space to alternative means of mobility, restricting freedom of walking/cycling and other leisure activities, contributing to the deterioration of the quality of life in Lebanese cities. In addition, the national and local government authorities responsible for managing the sector have unclear responsibilities and limited resources, which limit the potential for properly developing the sector towards better accessibility and higher efficiency and effectiveness.

Lebanon’s road transport sector

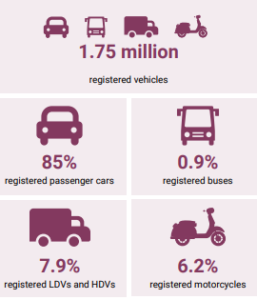

The report further explains the conditions of Lebanon’s transport sector affirming that road transport activity in Lebanon has seen rapid and continuous growth over the past two decades in line with population and economic growth. However, the growth in travel activity was not met with an appropriate development of the needed infrastructure and services. In fact, there has been no progress made on public transport by government authorities or the private sector since the end of the Lebanese Civil War in 1990, and no major initiatives to promote and enable alternatives to motorized transport across the country.

Mobility in Lebanon is almost exclusively dependent on motorized transport. When combined with high population density in urban areas, the reliance on motor vehicles contributes to high rates of traffic congestion compounded by the underdeveloped and poorly maintained roadway infrastructure, which slows down traffic.

One of the most negative impacts of the unsustainable motorization trend is the lack of consideration to non-motorized road users: walking and cycling have become extremely unattractive, even unsafe options.

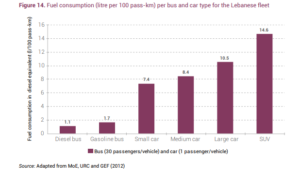

All this situation translates into rising energy consumption in road transport, which in Lebanon is overwhelmingly powered by fossil fuels. And the more fuel is consumed, the more emissions are discharged into the atmosphere which are a major contributor to global warming and climate change, affecting of course also human health. Furthermore, older vehicle models are responsible for higher energy consump tion due to the inefficiency of their outdated engine technologies.

tion due to the inefficiency of their outdated engine technologies.

In addition to that, road rehabilitation projects in Lebanon are generally poorly executed or not adequately targeted where in fact needed, resulting in wasting public resources.

Inadequate bus system and absence of rail

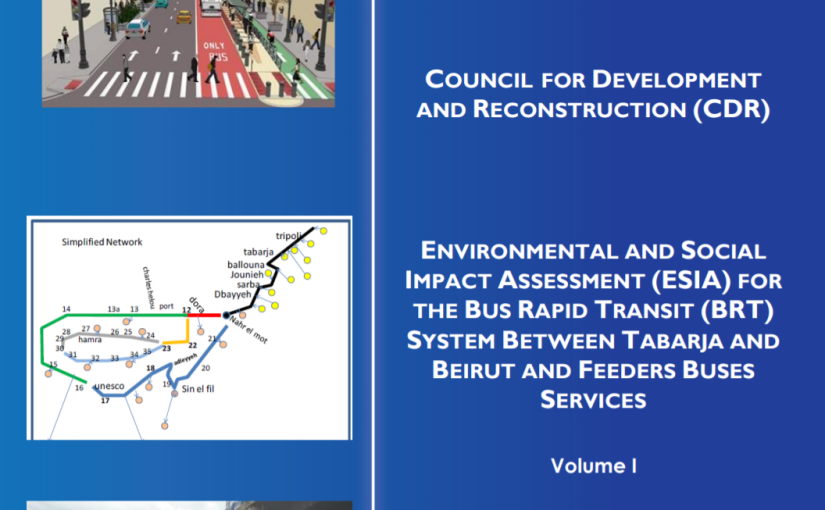

The public transport system in Lebanon was largely destroyed during the country’s civil war. As a result, the railway system became completely inoperative and all attempts to revive it have not been concretized.

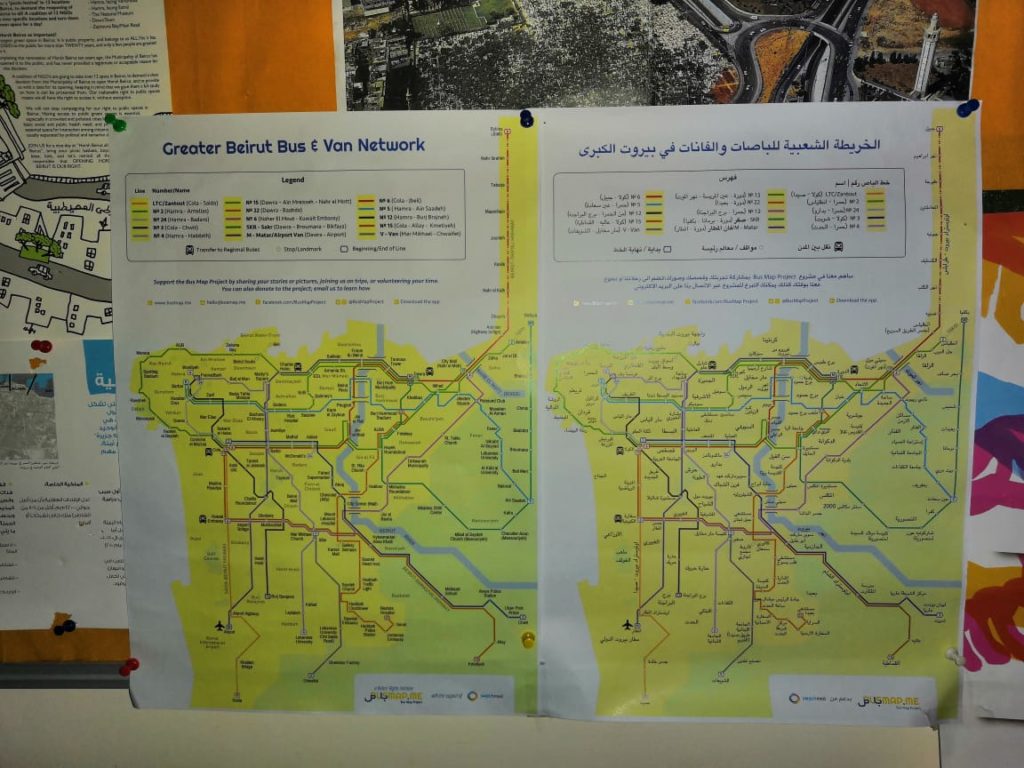

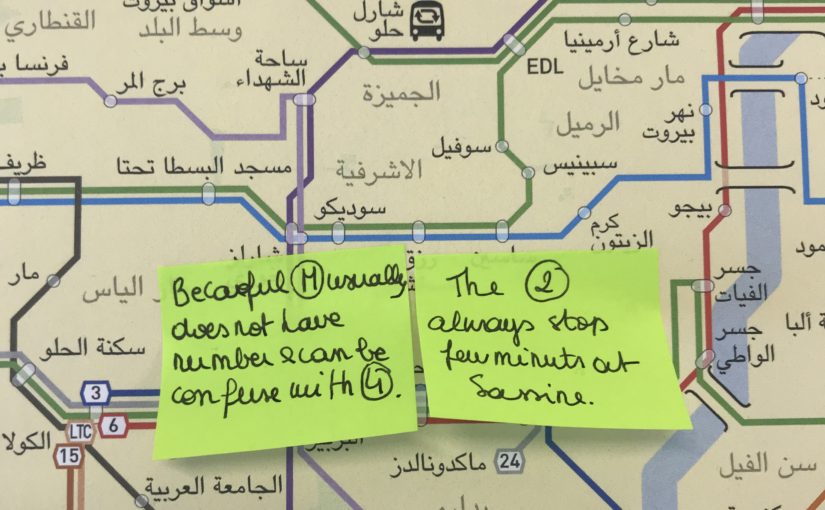

The major share of mass transport in Lebanon is claimed by taxis and shared-ride taxis (known as “service”), in addition to other providers, such as Uber and Careem, private minivans and buses.

Are missing any measures, equipment or infrastructure to make public transport easily accessible to the elderly, people with disabilities and other vulnerable groups. This situation is due in large part to lack of vision and strategy necessary for proper planning and development of Lebanese cities and the transport sector, compounded by administrative mismanagement of the public transport system.

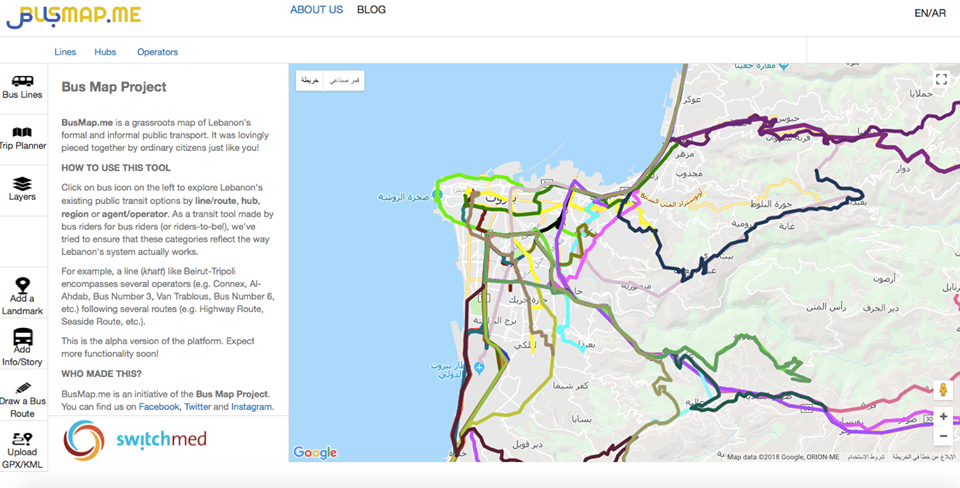

Public transport development remains very weak and mostly confined to projects in the GBA and Tripoli. In absence of a national public bus service that connects urban and rural areas, some smaller regional initiatives by municipalities and the private sector are emerging to fill the gap.

Fragmented institutional and regulatory framework

The UN-Habitat report denounces how inadequate institutional framework has contributed to a number of direct and indirect adverse consequences on the transport sector.

In Lebanon, there is no central authority responsible for the land transport system, which is the main factor behind the absence of a holistic national transport strategy. Having responsibilities dispersed among various stakeholders, sometimes with overlapping mandates, also leads to conflicting plans and decisions and delays in the implementation of actions. In addition, there is a lack of coordination between agencies even within the same ministry, weak integration of project activities between funding, implementing and operating agencies across different ministries, and a total absence of comprehensive urban transport and land-use planning.

Mobility challenges and opportunities in Lebanese cities

The guide makes it clear: mobility is all about the ease of access to destinations, opportunities and amenities, which is achieved through a variety of efficient and affordable choices of transport modes. Therefore, mobility reflects the freedom people have to move and to have goods transported in a convenient and efficient way in order to accomplish their social and economic needs.

Lack of walking, bicycling spaces and poor road safety

Most cities in Lebanon have become unfriendly to cyclists and pedestrians. Some traffic-calming measures are commonly used in Lebanon, in particular speed bumps on internal roads to slow down traffic. However, these measures very rarely involve urban land-use planning and regulations, which are most effective for calming traffic as well as for reducing car dependence. At the same time, the chronic lack of enforcement of traffic laws encourages motorists to drive recklessly and at high speeds, which in turn poses a high risk to cyclists and pedestrians and discourages alternative forms of mobility.

Some of the popular initiatives already launched by NGOs can serve as a starting point for spreading a walking culture. Several pilot designs for walking trails in the GBA have also been completed and await implementation. Also, bike-to-work and other campaigns and bicycling events have been organized by municipalities, the private sector and professional biking clubs across Lebanon to promote the adoption of bicycles for mobility. All of these have fostered a biking culture that can help propel the bicycle beyond a recreational and sports activity into a reliable form of mobility.

Lebanon’s NUP policies

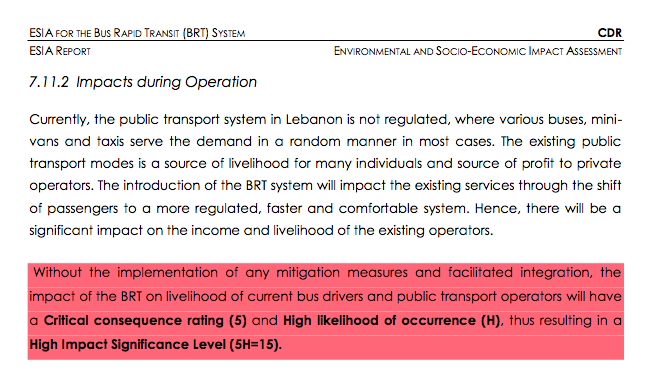

Based on the diagnosis of the challenges and opportunities for the transport and mobility sector in Lebanon, the UN report affirms that policy recommendations should be proposed to transition the sector towards sustainable mobility trends and should cover different types of interventions over the short-, medium- and long-term. This may require the development of human resources in the public sector, in addition to engaging the community in the planning process and to integrate bus drivers currently operating the informal system into any new public transport system.

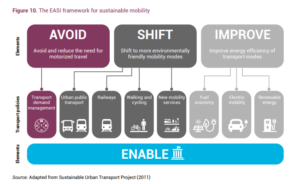

The Enable-Avoid-Shift-Improve (EASI) framework for policy formulation

The strategies and policy initiatives for planning future mobility considered most useful are those that focus on upgrading the quality of public transport services, improving traffic flow through better roadway networks, and enhancing mobility through encouraging walking and cycling.

The EASI policy framework for sustainable mobility is considered most appropriate. This framework is “inspired by the principles of sustainability” and “focused on the mobility needs of people”. The framework covers a wide range of policies based on “avoiding” unnecessary trips, “shifting” to more efficient transport modes, and “improving” trip efficiency. The “enable” component is based on supporting state institutions.

“Enable” policies

The “enable” approach is the application of policies and strategies to establish an effective governance system for the transport sector, with proper institutional frameworks that can support regulatory reform, capacity-building, financing and management. These enabling policies are especially important for the case of Lebanon, due to the weak and limited capabilities of state institutions.

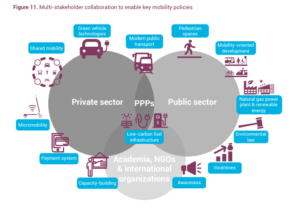

The report affirms that a blueprint is first needed to identify all needs and demands, set clear objectives, and develop comprehensive solutions to meet these objectives. This blueprint is the government’s national sustainable transport strategy that is still lacking in Lebanon. Moreover, since state institutions currently lack the human and financial resources for developing modern transport, the state must engage the private sector with public–private partnerships not only to implement projects, but also to operate certain services. Awareness campaigns will be needed to enable a massive transformation in culture and to fight resistance to change, as well as to raise enough political support.

“Avoid” policies

The “avoid” approach is the application of policies and strategies to eliminate or reduce the need for individual motorized travel. This approach is based on the realization that allowing the continuous increase in travel demand is unsustainable, and that measures to reduce motorized demands are less costly than those for increasing roadway capacity.

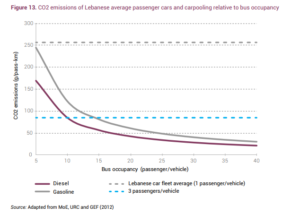

For example, a useful measure for Lebanon is carpooling, as it helps to avoid unnecessary motorized trips per person and offers an intermediate solution to the severe congestion conditions. This translates also to a significant reduction of CO2 emissions.

“Shift” policies

The “shift” approach is the application of policies and strategies to transition travel from costly, high energy-consuming and polluting modes, such as motorized means, towards cheaper, more efficient and environmentally friendly ones, such as public transport. The “shift” policies do not eliminate or reduce trips, but they seek to make travel more sustainable.

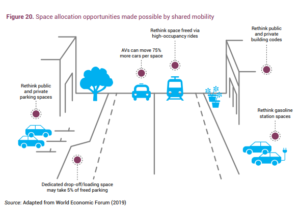

The most efficient non-motorized means of transport are walking, cycling and micromobility, since these modes provide the highest energy savings, environmental and cost benefits. Shifting to these alternative mobility means can also help to reclaim urban spaces away from roadways and large parking areas. But the most beneficial shift is to public transport, because of its mass scale potential in removing cars from the roads. In particular, rail transport can be considered as the most efficient option, due to its high transport capacity per trip.

“Improve” policies

The “improve” approach is the application of policies and strategies to advance the energy efficiency of vehicle technologies, and to use cleaner alternative fuels and sources of energy in order to improve trip efficiency and reduce the emissions of the transport system.

The first beneficial strategy under this approach is to replace older vehicle models, which are heavy polluters. The most beneficial “improve” strategy is to provide tax subsidies in order to encourage the transition to electric vehicles which present the highest savings in fuel consumption and emissions, but for higher purchase costs.

Future trends for sustainable transport and mobility

Vehicle electrification

The sharp rise in the price of oil at the turn of the century, along with the impacts of transport emissions on human health and the environment, motivated a major shift to cleaner alternative fuels and more efficient vehicle technologies. Primary among those innovative technologies are electric vehicles, due to their advanced technology, their relatively affordable costs, and their ability to reduce emissions.

Micromobility

Micromobility devices are emerging as a practical alternative to cars in urban areas and as a supplement to public transport. Noteworthy is the potential ability of these devices to help cities address the major challenge of air and noise pollution from road traffic, as they can also serve as a sustainable mitigation approach thanks to their zero emission footprint.

These capabilities come however at an additional financial cost. These costs are expected to go down in line with decreasing battery costs, and even further as micromobility achieves economies of scale.

Other challenges facing the user adoption of micromobility devices include their limited usability in bad weather conditions and by the elderly and disabled commuters, the lacking storage capacity for carrying items, and their vulnerability to theft.

Connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs)

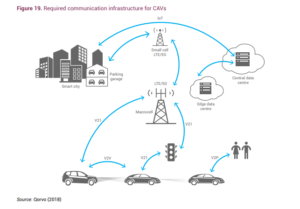

These vehicles rely on advanced automation technologies that will change the way people interact with cars and other transport means, while also making cities smart.

CAVs are expected to have more optimal energy consumption, contributing to a considerable decrease in air pollution. Most notably, they can provide increased mobility for people with disabilities and the elderly.

For the long term, public authorities need to plan for the paradigm shift that CAVs are expected to bring to passenger transport through autonomous shared mobility.

Shared mobility

Shared mobility refers to the shared use of any transport mode through an easy, fast and affordable access model. Combining new digital technologies with innovative business models, shared mobility today includes the use of mobile applications.

Another key aspect of shared mobility is sharing micromobility devices for short trips: including bike sharing and scooter sharing.

Conclusion

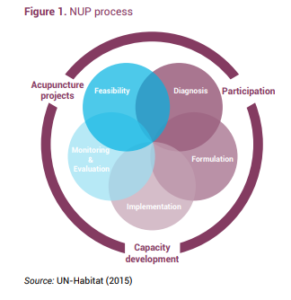

According to the global NUP Guiding Framework, policy formulation consists of evaluating policy options, formulating policy proposals, building consensus, assessing institutional capacity, in addition to researching implementation, monitoring and evaluation practices in preparation for the policy implementation phase.

The policies designed through the program seek to transition the transport sector to a sustainable future by (1) minimizing unnecessary travel, (2) reducing reliance on motorized models by enabling walking and bicycling and discouraging the use of cars, (3) shifting to public transport and the use of micromobility devices, (4) improving the efficiency of vehicle technologies to reduce the use of polluting fossil fuels, and (5) reducing mobility costs.

There is an urgent need to implement proper urban and transport planning policies and strategies aimed at reducing motorized vehicle trips. Such measures would directly lower travel time, congestion, fuel consumption and emissions, and indirectly lower the risk of accidents.

A national strategy for sustainable transport is a critical element for an effective transition to sustainable mobility. Such a strategy should necessarily include a project of the needed policies, involving infrastructure development, mitigation actions, incentives and disincentives, and awareness raising. Implementing these policies will require overcoming barriers such as: lack of political will, lack of data, lack of transparency, limited government resources, lack of inclusion of vulnerable groups and deeply rooted behaviors and practices.

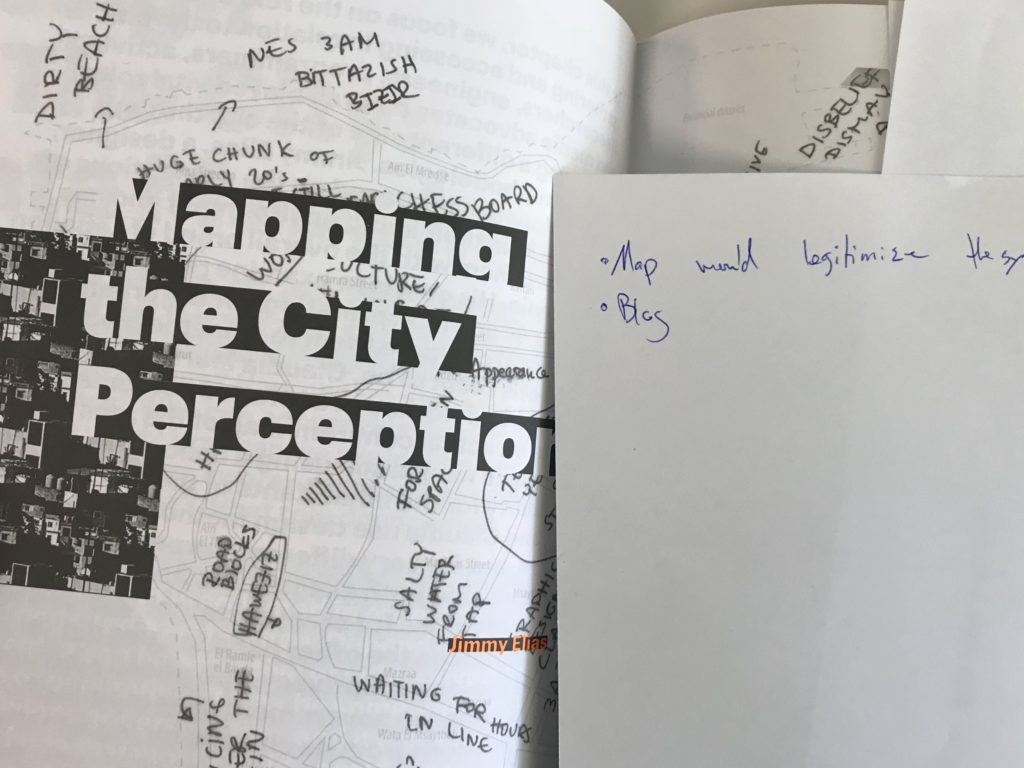

In light of the current political and economic crisis facing the country with widespread public demands for government reforms, and given the strong involvement of civil society in awareness-raising and capacity-building activities, there is an urgent need for creating a transparent process for citizen participation in urban transport planning.