To what extent is it appropriate to formally map an informal system? Can collective mapping help spark new ways of thinking about public transit in Lebanon? These are some of the questions raised by Bus Map Project’s participation in Beirut Design Week this year, when we launched our second prototype bus map of Greater Beirut and the alpha version of our online transit platform BusMap.me, a participative tool that seeks to crowdsource, clarify and spread information about the people, places, voices and traces of Lebanon’s transit system. Will you join us on board?

By Mira Tfaily and Jad Baaklini

June 23, 2018. Photo by Moussa Shabandar

Slow-Hacking Beirut’s Bus Map

Beyond the brute fact of mapping, Bus Map Project has always been driven by a desire to disrupt the traditional talking-points around public transport in Lebanon. Our project is patient and incremental because it insists on a fresh perspective on urban change. By making visible the range and regularities of our ubiquitous yet little-understood transit system, our map is trying to prove a point; it is advocacy by other means. And what it demands is that we start taking this transit system more seriously.

Yet, in doing so, the bus map tends to hog the spotlight as an artifact — a solid, already-accomplished matter of fact — pushing these motivating questions into the background, like any utilitarian tool eventually does. How, then, can we (re)turn the map, from an object of design, back to a matter of concern and a locus for civic action? How do we keep its point — its advocacy by other means — at the forefront?

More importantly, how do we keep this traffic flowing both ways? From tool to platform and back again, how do we break the silos between expertise and experience (design and ridership) to widen the sense of shared ownership to encompass as many civic actors as possible?

As part of Beirut Design Week, and in partnership with Public Works Studio through their Forum on Cities and Designers, Bus Map Project had the incredible opportunity to organize a workshop on June 23th, 2018, entitled “Slow-Hacking Beirut’s Bus Map.” The idea of “Slow-Hacking” — coined at first in jest by Public Works’ Monica Basbous — came out of our concern for making sure that this map that we’ve been lovingly piecing together, route-by-route, for a while, remains an open question: open to change in itself, and open by catalyzing debate over the cities we live in and reproduce every day. The word is meant to appropriate the can-do attitude of hackathons — that helpful sense of agency and confidence that we want to see more of in urban advocacy in Lebanon — while rejecting the less helpful sense of misguided urgency and false efficacy behind the fantasy of quick fixes.

Over the course of three hours, we attempted to prefigure the slogan recently displayed on the state’s own buses (“shared transport is a shared responsibility”), while inviting participants into our process. Through an interactive presentation, we shared Bus Map Project’s view of mapping as a form of activism — the kind that not only pushes for recognition of the existing system of transport now marginalized within the dominant doxa, but that also stirs up conversations about the mobile inequalities that traverse it.

We tried to keep our presentation anchored in ourselves, as riders and advocates. We shared the context of our own meandering journeys into the project: Chadi’s early development work in 2008, Jad’s research and activism interests in 2010, Sergej’s work with Zawarib in 2012, and Mira’s journalistic introduction to our work in 2016 before joining as a researcher in 2017. From this personal and collective perspective, a lot has changed since the seed was first planted when someone once said that creating a bus map for Lebanon was one step too far (because a map would legitimize something ‘substandard’). Today, very few people will argue that public transport doesn’t exist in Lebanon — the lacuna where it all began.

From that point of view, much of our work is done; thank you for tagging along, and we hope that by foregrounding the ordinary ways that our personal stories became entangled in the politics of this often-mystified thing called the city, this small project can serve as a case study that inspires you and others to adopt similarly incremental approaches to seemingly intractable problems.

From a wider perspective, however, our work has only just begun. And we need your help to keep moving forward.

Photo by Chadi Faraj

Whose Streets? Our Streets

The workshop participants came from diverse backgrounds (architects, GIS specialists, urban planners, graphic designers, etc.) but shared overlapping interests. We opened the session by asking everyone to share their understandings of, and experiences with, Lebanon’s buses. Some came to the event with a lot of experience riding transit; others were curious and wanted to learn more. Some had initiatives of their own, like a WhatsApp group to share information with newcomers on how to get around Lebanon by public transport and a “mobility transformation” Meetup.

This personal approach helped us keep the discussion rooted in the city as a lived experience, far from the technical abstractions that create artificial and disempowering distance between our reality as ordinary practitioners and the infrastructures we help reproduce every day.

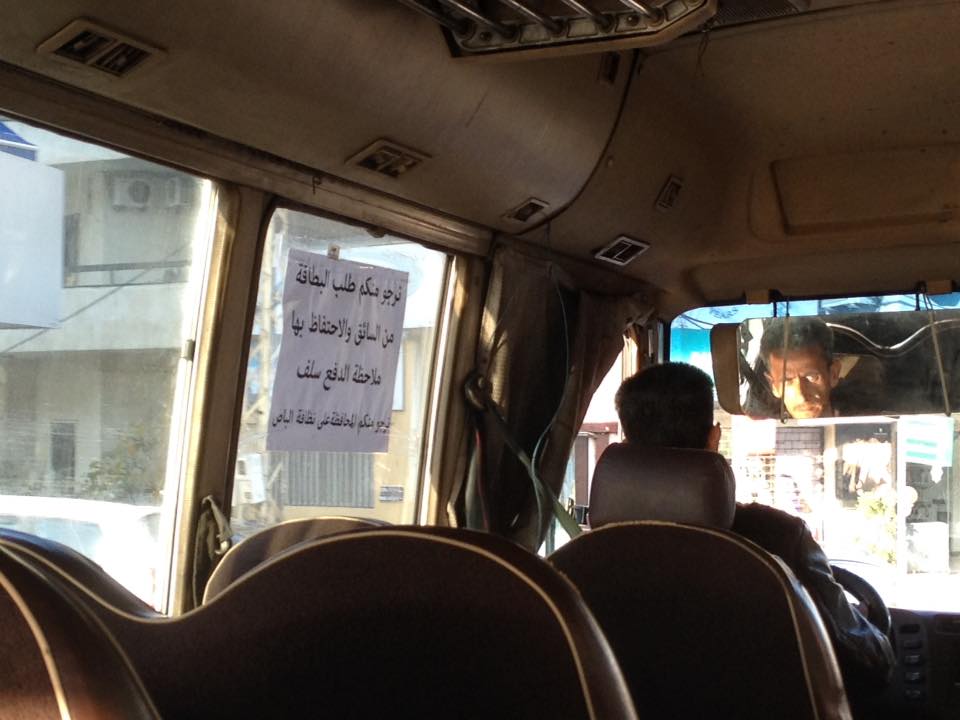

To emphasize this idea, our presentation of the basic features of Lebanon’s transit system turned the usual definition of public transport on its head: instead of starting at ‘the top,’ drawing conceptual contours and differentiating ‘para-‘ from ‘-transit’ proper, we privileged the concrete reality of riders first: their flesh-and-blood facticity, their cosmopolitan diversity, their eyes looking directly into yours, demanding recognition and ‘equal access’ to visibility.

When we put things in this way, we swerve very close to romanticism. That’s fine. This is because the simple profundity of the person is the foundation of everything we do. From this understanding, we define public transport as first and foremost a transport public. From that, we branch out and begin to notice the spaces of conviviality that connect user to operator, bus to system, street to map. On this foundation, we clarify our shared stakes in combatting misinformation and stigma (that perennial problem that we mustn’t underestimate) and keeping transit advocacy rooted in real lives and livelihoods. Only then do we dare to offer definitions.

Lebanon’s transit system is best understood as a network of networks, gelling together along several spectra of agglomeration and ownership:

- state-owned (OCFTC) ↔ municipally-owned (Ghosta, Dekwene) or organized (Bourj Hammoud)

- corporate (Connexion, LCC, LTC/Zantout…) ↔ family businesses (Ahdab, Sakr, Estephan…)

- route associations or fleets of a few owners with shared management (Number 2, Number 5, Van 4…) ↔ loose networks of individual operators (Number 22, Bekaa Vans…)

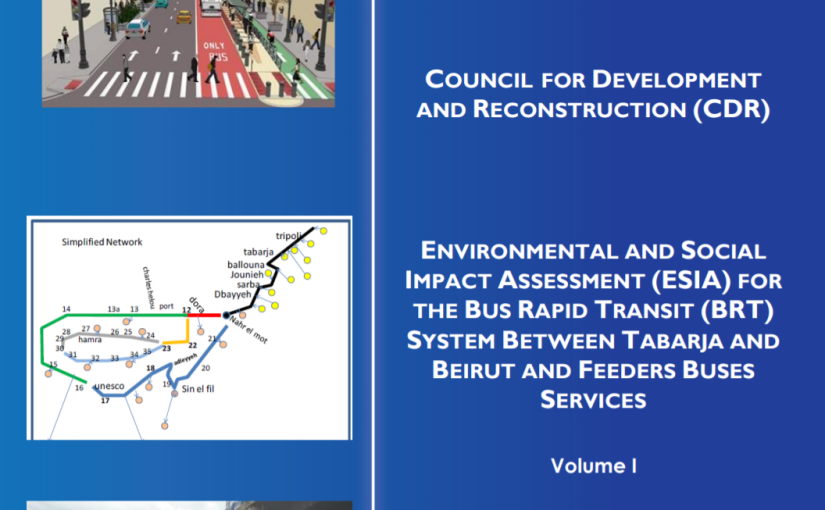

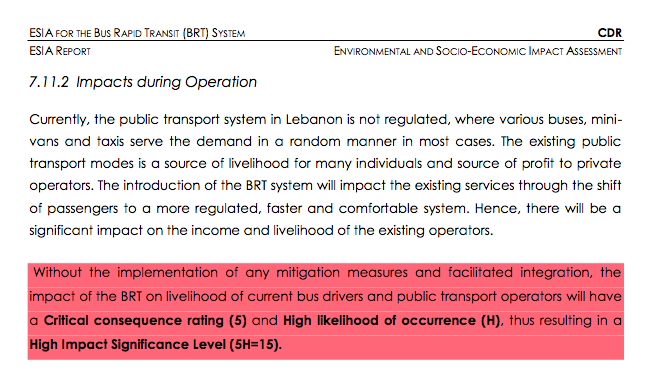

When our discussion turned to these concepts, a lot of debate was sparked, including a conversation on the controversial BRT system that we’ve blogged extensibly about. Hence, one consequence of taking the existing system seriously — people first, places second, conceptual categories last — is making the question of working with what exists (joud bel mawjoud) much more realistic and pressing. Why can’t we invest in existing people?

Connecting the Map to the City

After the presentation, everybody was invited to pitch in and make our map their own: What would they add? How would they represent informal landmarks? What changes would they propose to make the map more accessible?

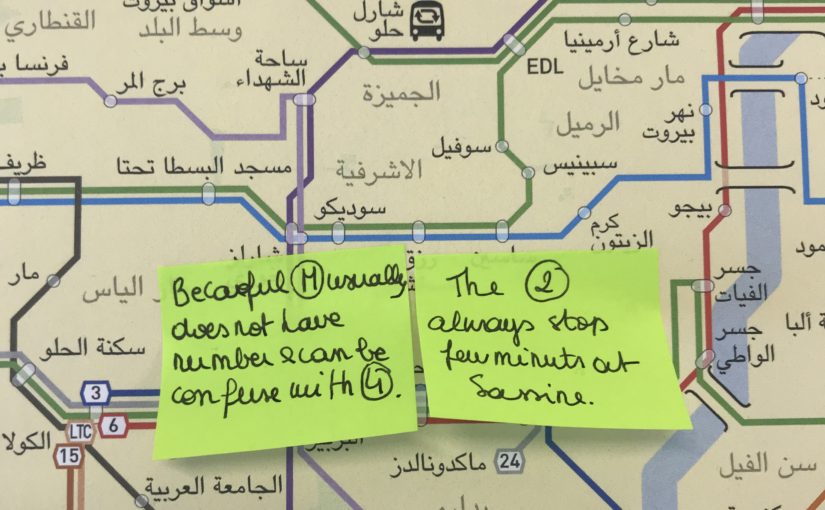

Many participants thought that the Number 5 and Number 2 bus were the same, when the two lines separate at Sassine heading north. Misapprehensions like this point to the importance of involving more and more people from ever-wider circles in this collective project; indeed, the majority of us agreed that collective and incremental design can be a powerful language and tool for encouraging a change of mentality needed to shift our society towards more sustainable and just mobilities. June 23 was Day 1 of hopefully many more in this new phase in our project, and we will continually look for more ways to involve as many people as possible in the making and hacking of our collective output.

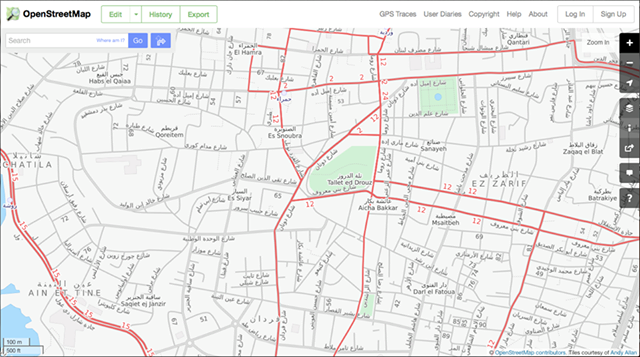

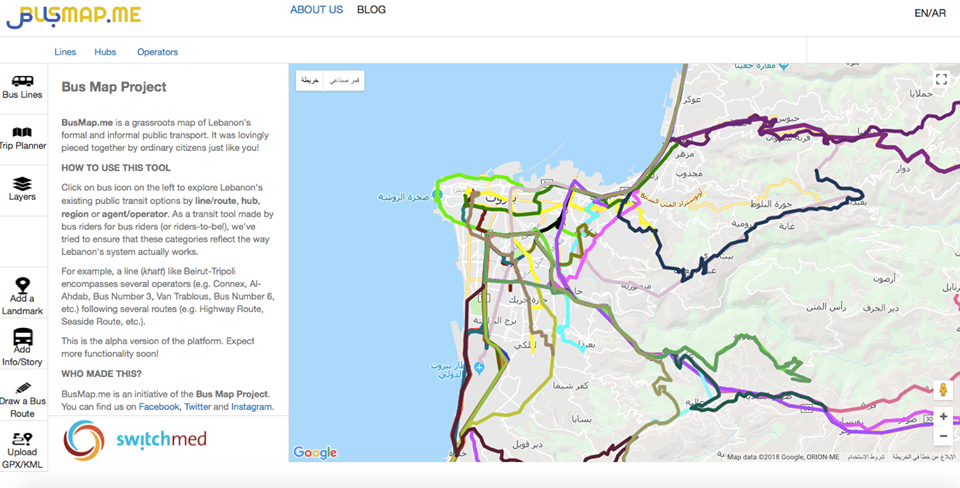

One tool we hope will facilitate this is our online participative platform (BusMap.me), launched during the workshop. It’s still in alpha development, but we’re so happy to finally make it public — a big thank you goes out to Chadi and our grassroots mappers for their hard work! BusMap.me aims to become a hub for crowdsourcing GPS data and annotating Lebanon’s transit routes with photos, tips and stories — material that can’t fit into a single, static bus map, but which is pretty much the essence of mapping our word-of-mouth urban geography, Lebanese-style.

The platform is imperfect and incomplete by design — and we mean it when we say that this is by design; we refuse to wear the crown of authority over this endeavor and proudly wave the banner of engaged amateurism in the city, with stubborn determination — because beyond mapping, the platform is meant to be an invitation for people to engage with shaping the system, contributing what they can to a collectively-owned map that celebrates the cacophony of voices that constitute Lebanon’s transit system. Think you can do better? Get in touch!

Our involvement in the Beirut Design Week continued on June 26th, 2018, when Sergej presented our work and his design process during a roundtable organized by Public Works entitled “Between City and Studio: Connecting the Map to the City”. Building on the previous participative workshop, he emphasized the activist role of the mapper and map designer. Every map is a collection of choices — deciding how and what to display influences the collective imageries and tropes that either challenge the established urban mythology, or, on the contrary, contribute to furthering the gap between urbanist discourse and lived reality. Mapping is and should remain an open question and we hope that more and more people recognize and join this political process that we are catalyzing.

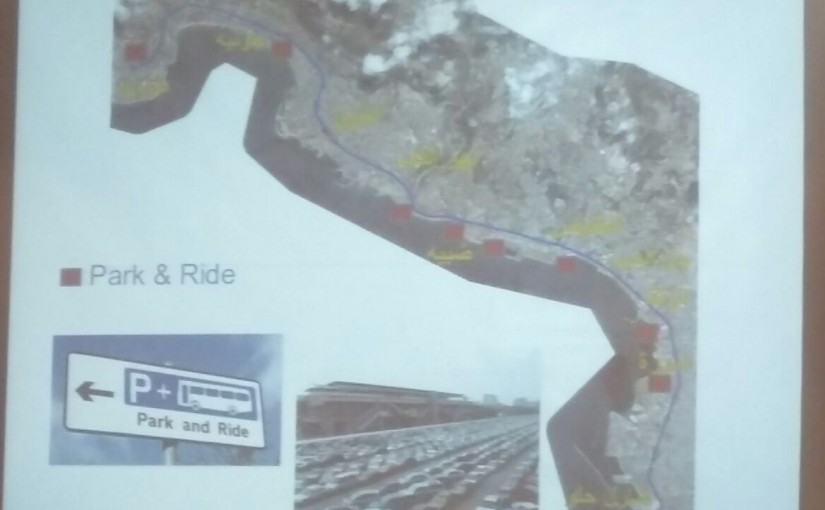

Later that week, some encouraging signs of this happening emerged! We had the pleasure of attending YallaBus’s first meet and greet, where they facilitated their own participative discussion to debate the mapping of Lebanese bus routes, and presented the first version of their transit app. Taking inspiration from our work and building on our second prototype, YallaBus has started working on their own static map; during the event, attendees also came up with new and exciting solutions to face the challenges of mapping and visualizing an informal system.

We also took the opportunity to raise some questions about YallaBus’s release of the live GPS feed of Number 2 in Beirut. While we are excited to see progress in this live-tracking work, this beta release poses privacy and security concerns, since the location of buses (and, presumably, the homes of bus drivers) in the initial release was on display, potentially endangering the drivers. We are happy that YallaBus has been open to such feedback and look forward to seeing how their app develops.

We are also enthusiastic to see more events and gatherings of this type happening in the future. Let us keep catalyzing the change we want to see! Proactively, pragmatically, sometime’s poetically — our cities are ours for the (re-)taking.