On October 25th and 26th, we had the pleasure and honor of being invited by Dr Tammam Nakkash to a symposium organized at the Order of Engineers and Architects called “Towards Organized Public Transport in Lebanon.”

في ٢٥ ت١ ٢٦ ت١ ٢٠١٧ ، لقد كان لنا الشرف بتلبية دعوة من قبل الدكتور تمام نقاش للمشاركة في سيمبوزيوم في نقابة الهندسة في بيروت بعنوان ” نحو نقل عام منظم”.

We were first introduced to Dr Nakkash almost seven years ago, as a keynote speaker in an event called “Public Transportation, Public Concern,” where he lectured on all the necessary, institutional prerequisites to transport sector reform in Lebanon. The message he clearly articulated that day in December was that there were no apolitical quick-fixes to introducing new transport modes in the country, and in doing so — in calling for real “champions” of public transport — Dr Nakkash helped plant the seed for what eventually became the Bus Map Project in 2015. So for that alone, we are thankful for his interest in our work today.

كنا قد تعرفنا الى دكتور نقاش منذ حوالي السبع سنوات كمحاور رئيسي في مؤتمر “النقل العام شأن عام” حيث حاور بكل الحاجات الاساسية من قوانين واجراءات لاعادة الاعتبار للقطاع النقل واعادة تنظيمه. وقد اعلن بشكل واضح ان لا حلول سياسية سريعة –.

فبهذا، ومن خلال دعوته الشبابية ل “الأبطال” في احياء القطاع، يكون الدكتور نقاش زرع البذور الاولى لما اصبح يعرف بمشروع خريطة الباص في ال ٢٠١٥. لذلك نشكر اهتمامه في مشروعنا اليوم.

The other important detail we remember from that day in Masrah el-Madina was a question posed by the only politician in attendance, MP Ghassan Moukheiber, who, after listening to the problems of congestion in Beirut and the bright visions of Bogota, politely yet firmly asked to hear more about the existing transit situation in Lebanon. The panelists had very little to say. One speaker admitted she had taken a bus in Beirut only once in her life, having vowed to never repeat it, because it was too slow.

الشيء الاخر الذي يجب ذكره عندما نراجع ذكرياتنا في مسرح المدينة هو سؤال من قبل السياسي الوحيد الذي كان حاضرا، النائب مخيبر، عن نظام النقل الموجود فعليا الان في لبنان، وذلك بعد استماعه لمشاكل زحمة السير والحل الذي حصل في بوغوتا وغيرها من المدن النموذجية. فالمحارون كان لديهم القليل ليقلوه حتى احد المحاورات قد اعترفت انها اخذت الباص مرة واحدة فقط في بيروت طوال حياتها وانها لن تعيدها مرة اخرى بسبب بطئ الباص.

Fast forward to 2017. The two-day event at the OEA began with a recurring leitmotiv that made us feel that plus ça change in the way that the “public concern” of public transport was conceived. “Detailed and updated plans to implement change in Lebanon have been studied for over 10 years,” we heard again and again, “but what has been failing dramatically is the enforcement and implementation.” From there, the different panelists and discussants focussed on the different ways to break through this institutional barrier of policy immobilism. Dr Nakkash’s presentation dove into more details about the causes of the status quo of stasis in Lebanon. Suggesting concrete solutions to address some very specific issues (e.g. architects and engineers who participated in the construction of buildings on lands owned by the OCFTC should be invistigated), he also highlighted one of the main problems of transit in Lebanon: the tie between transport funding and the government, that makes any plan correlated to possible institutional instability and lack of political will. This was one of the same prerequisites he had spoken about in 2010.

فلنعود الى ال ٢٠١٧ والى النهارين في نقابة الهندسة اللذان اعطا انطباع الى اعادة الاهتمام الى قطاع النقل من قبل المجتمع عامة والمهندسين والمختاصين خاصة. اكثر من عشرة سنوات ونسمع ان هنالك دراسات وخطط ومخططات للقطاع تدرس تعدل ولا تطبق. من هنا حاول المحاورون شرح ومناقشة السياسات التى جمدت هذا القطاع والعقبات التي وقفت في تطوره.

محاضرة الدكتور نقاش حاولت الغوص في تفاصيل هذا الوضع مقترحا حلول عملية لمواجهة بعض المشاكل (كأقتراح العمل على سحب تراخيص المهندسين الذين شاركوا في التعدي على املاك مصلحة الحديد والنقل المشترك). وشدد على مشكلة من المشاكل الاساسية للقطاع النقل في لبنان وهي الربط بين ميزانيات النقل والحكومة التي تعاني من عدم الاستقرار وعدم ايجاد الارادة السياسية لتطوير القطاع .وهذا ما كان صرحه في محاضرته في ال ٢٠١٠.

Nakkash elucidated how he had been suggesting for years a simple solution to the imbroglio of overlapping responsibilities between the OCFTC, the Ministry of Public Works and Transport and the municipalities: the creation of a higher, centralized transit authority that would bypass the frustrations and disentangle the bureaucratic knots by having its own fund, separated from the government’s budget, which only conspires to suffocate projects at birth. One example he gave was the rejection of the BRT plans by the Municipality of Beirut: in his view, the presence of an independent transit authority would bring consistency to transit strategies.

نقاش صرح واعلن كم يعاني لسنوات من تضارب الصلاحيات بين الادارات والوزارات ومصلحة السكك الحديد والنقل المشترك والبلديات المسؤولة عن القطاع، وانه منذ زمن طالب بأنشاء هيئة مستقلة مسؤولة للنقل لديها كل الصلاحيات لتكسر البيروقراطية الموجودة وتتمتع بأستقلال مالي تستطيع من خلاله تمويل طول مدة مراحل المشروع، من التخطيط الى التنفيذ الادارة اليومية حتى لا تموت المشاريع في مهدها كما يحصل الان. واحد الامثلة الذي اعطاها رفض مشروع الباص السريع من قبل بلدية بيروت ومن وجهة نظره وجود الهئية المستقلة للنقل سيعطي قوة وتكامل لخطط واستراتجيات النقل.

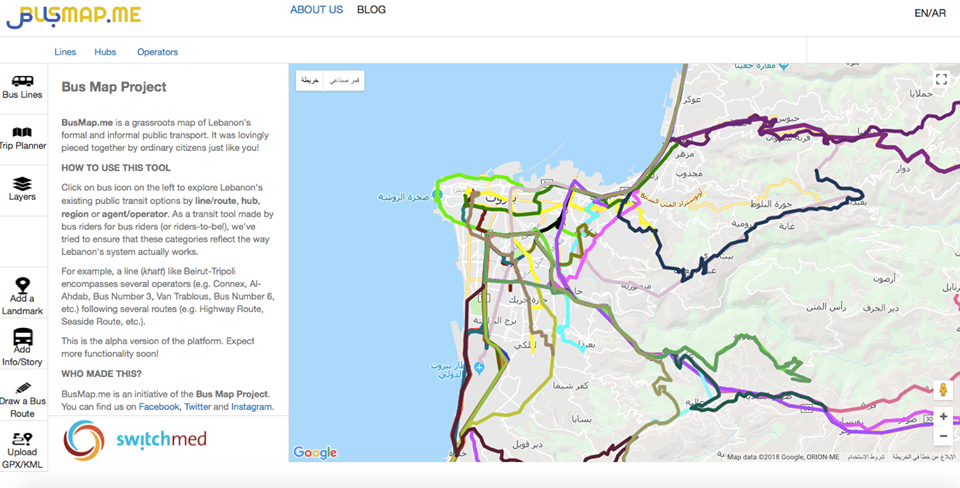

While it was inspiring to see Dr. Nakkash’s tireless fight to save policymakers from themselves, the issue that was most pertinent from our perspective was his challenge to the mainstream definition of public transport that we often hear in casual and even activist conversations: “Public/Shared transport is not defined by the entity who owns it and operates it.” Rather, Nakkash argued that public transport is characterized by fixed routes, fixed stops, fixed schedules, and access for everybody in exchange for a fee. While this definition of public transport may seem to exclude Beirut’s existing transit at first glance, it certainly opens up much more room for understanding how this system fills many gaps — and hence, meets most criteria — of more formal systems.

ورغم كل الجهد الذي صرفه الدكتور نقاش في المؤتمر لمحاولة تبيان العجز السياسي والتنظيمي في منظومة النقل، الا اننا يهمنا بشكل خاص اظهار تعريف النقل المشترك او العام او العمومي حسب ما عرفه دكتور نقاش والذي لطالما كان موضوع جدل بين الناشطين في القطاع.

فعرفه بأن النقل العام او المشترك او العمومي و هو نقل لا يهم صفة ملكيته او تشغيله، اهو قطاع عام او خاص، انما هو النقل على خطوط ثابتة محددة مسبقا يتم الصعود والنزول في محطات محددة ويعمل حسب جداول و توقيتات معلنة واستعماله متاح للجميع الراغبين يشتركون مع غيرهم مقابل بدل مادي. وهذا التعريف لا يستبعد النظام الغير رسمي المستعمل في بيروت بشكل كامل، بل يفتح المجال امام فهم كيفية عمل هذا النظام وملئ النقص والحاجات للناس ولديه الكثير من النقاط والايجابيات

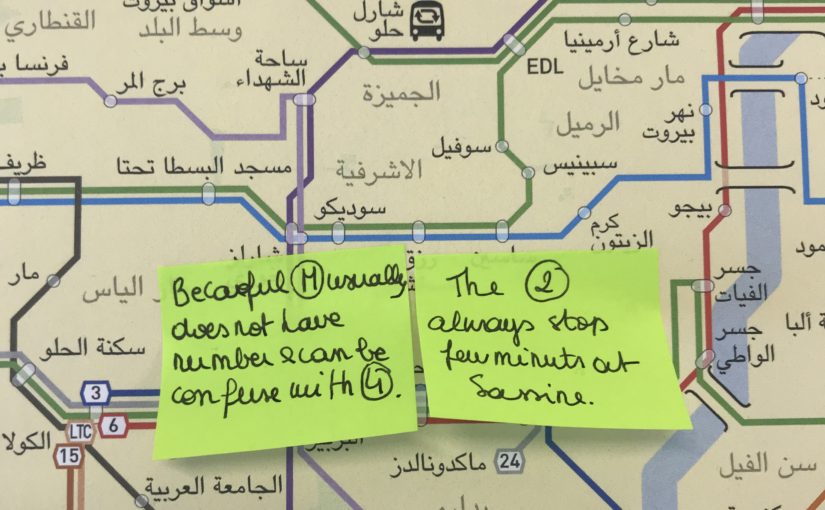

Using the example of the Van Number 4, which takes advantage of the unregulated environment to reach a dynamism that formal transport could never compete with, Nakkash called for the formalization of the line to a certain extent, and hence, acknowledged the need for planning for integration, and not exclusion.

إستناداً على مثال الفان رقم ٤ الذي استفاد من عدم وجود بيئة تنظيمة للقطاع والذي وصل الى دينامكية لا تستطيع الانظمة الرسمية التنافس معه فيها، دكتور نقاش طلب بأيجاد اطر تنظيمية لهذا الخط، والتوجه نحو الدمج وليس نحو العزل.

الاشخاص الذين يعملون على موضوع النقل المشترك في لبنان يجب ان يتعاملوا مع قطاع النقل الغير رسمي وكذلك في العالم اذ انها جزء من التحديات التي تؤثر على القطاع النقل والتنقل.

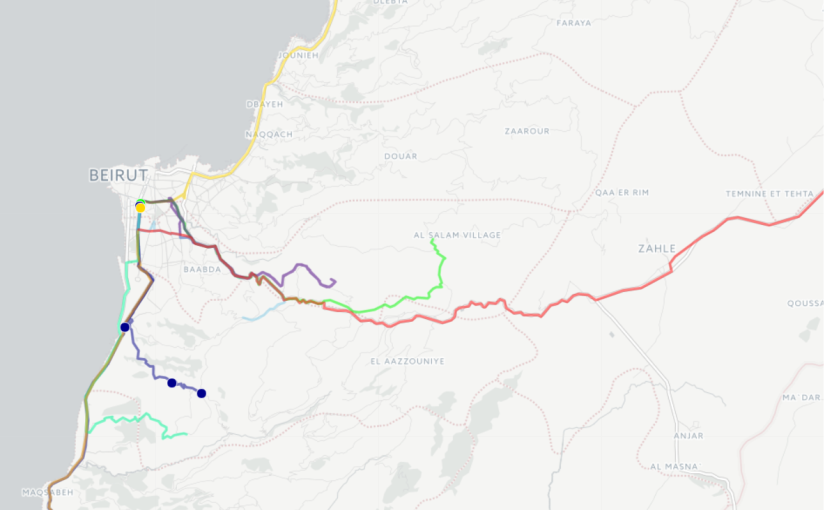

The people whose job it is to plan public transport in the MENA region and in Lebanon have to address the question of informality, as well as global challenges that affect transit and mobility everywhere. This is what Dr Ayman Smadi, former Director of Traffic and Transport at the Greater Amman Municipality and current Director of the MENA branch of the UITP, emphasized in his keynote speech. One of these challenges is the penetration of private companies like Uber or Careem in the transit market, a phenomenon that is more striking in a country like Lebanon, where transit is almost wholly run by private operators due to endemic state neglect. To what extent is it possible to create a holistic, national land transport strategy that integrates all the stakeholders from the public and the private sectors? The acknowledgement of the existing system is an obvious prerequisite, as well as a state vision that is transparent and which is as concerned with addressing sociocultural attitudes as it is on built infrastructure.

هذا ما تحدث به الدكتور ايمن الصمدي المدير السابق للنقل والسير في مدينة عمان والمدير العام للمتوسط في الاتحاد الدولي للنقل العام واكد عليه في مشاركته. واحد هذه التحديات دخول شركات الخاصة الى القطاع وخاصة اوبر وكريم وتأثيرها على القطاع خصوصا في لبنان حيث القطاع الخاص لديه اليد الطولة في تسيير الخدمات في ظل غياب الدولة.الى مدى نستطيع خلق خطة واستراتجية ناجحة تجمع كل الاعبين المساهمين في القطاع من القطاعين العام او الخاص؟ الاعتراف بالنظام الموجود هو خطوة مطلوبة واساسية كما رؤية الدولة مع الشفافية التي تواجه وتعالج االمشاكل الثقافية والاجتماعية لبناء البنى التحتية للقطاع.

Even though most panelists still saw our bostas, vans and minibuses as a temporary gap-filler that should be replaced, the fact of even acknowledging their existence in a setting like this was an important step forward towards integration. While seeing them as insufficient, Jad Tabet, presiding head of the OEA, listed these modes in the options available for citizens who want to get around the country: “There isn’t in Lebanon any choice for mobility except private cars, services, buses, vans.” Ramzi Salameh from the Road Safety Authority even took it one step further, encouraging the use of the actual existing system whenever possible.

جاد تابت نقيب المهندسين في بيروت صرح انه لا يوجد وسائل متاحة الان للاستعمال الا السيارة الخاصة,التاكسي والسرفيس والباصات والفانات وطلب بوجود انماط اخرى فعالة للنقل والتنقل .

وايضا هناك البعض من المتكلمين كانت ارائهم تتمحور حول قضية ايجاد بديل للنظام الباصات والفانات الموجودة الا ان ذلك نعتبره اعتراف بوجودهم وانهم يملؤون فراغ الموجود في القطاع بتقديم خدمات النقل وهذا اعتراف هام للدمج في المراحل اللاحقة.

As we pointed out in our presentation during the last panel, physical infrastructures and technologies alone are not sufficient for implementing sustainable change. This was further emphasized by Wissam al Tawil, president of the Scientific Committee of the OEA, who said that policies only oriented towards improving infrastructures are doomed to fail. The issue of transport in the country is not only technical, but cultural. The omnipresence of car culture was widely debated by MP Mohammad Qabbani, who is a member of the parliamentary workgroup on transport issues. Dr Christine Mady from NDU broke down the definition of infrastructure even further, dividing it into four categories: physical, social, institutional, and information/technological. Hence, a holistic shift in all levels is needed to re-orient urban development towards transit use.

” ليس في لبنان حالياً خيارات أخرى غير السيارات الخاصة سوى سيارات الأجرة والفانات والباصات، ولا يوجد اليوم خطة متكاملة لتنظيم وسائل التنقل هذه تسمح بالحدّ من الفوضى وباحترام معايير السلامة العامة”.

رمزي سلامة امين عام السلامة المرورية اخذ الموضوع الى بعد اخر بأستعمال النظام الموجود والعمل على تحسينه.

كم ذكرنا في مشاركتنا في المؤتمر البنى التحتية المادية والتكنولوجيا لا تكفي لتغيير مستدام وهذا ما اوضحه واكده رئيس اللجنة العلمية لنقابة الهندسة وسام الطويل، الذي قال: السياسات التي تتبع مسار تحسين البنى التحتية المادية هي تفشل دائما ولا يتخيل احد ان حل مشكلة النقل تكون بتوسيع طريق او مد جسور. والمشكلة في موضوع النقل ليست فقط تقنية انما ثقافية. هذا ما اوضحه رئيس لجنة الاشغال والنقل محمد قباني. الدكتورة كريستين ماضي من جامعة اللويزة فصلت البنى التحتية الى اربع اقسام: مادية،اجتماعية، تنظيمية، وتكنولوجية ودعت الى التحول الى التخطيط العمراني على شكل التنمية نحو العبور transit oriented development الذي يؤدي الى شعور الانتماء للمجتمع ويسهل الولوج الى الخدمات العامة.

In conclusion, we reiterate that the problem of (im)mobility in Lebanon cannot be solved through a set of top-down policies that keep ignoring the existing transit system and the daily livelihoods and reality of thousands of riders and workers that it represents. The OEA symposium has brought to the fore the obstacles preventing the implementation of a national transport strategy; but shouldn’t the first step for change be the use of the available and functioning transit system of the country?

في الخلاصة نكرر ان مشكلة النقل والتنقل لا يمكن حلها بسياسات تغيير فوقية تتجاهل النظام الموجود وحياة واقع الكثير من الركاب والسائقين العاملين في هذا القطاع، والذين لهم الحق في ابداء رأيهم ويكونو شركاء في القررات. وقد ابرزت الندوة في نقابة الهندسة العقبات التي تحول دون وجود استراتجية وطنية للنقل؛ لكن الا يجب ان تكون اولى الخطوات لها استعمال نظام النقل الموجود الفعال في البلاد؟

Dr Mona Fawaz from AUB closed the symposium on this note, with these very encouraging final words: “Decision makers need to be convinced by the culture of public transport. The main point that came out of these two days is that there indeed is an existing system and we need to use it when we can, because this is the first step towards change.”

الدكتورة منى فواز من الجامعة الاميركية لخصت السيمبوزيوم بهذه العبارات المشجعة: “المسؤولين يجب ان يقتنعوا بثقافة النقل المشترك. والنقطة المهمة بعد هذين النهارين هناك نظام موجود وندعو الى استعماله عندما نستطيع لانه هذه اولى الخطوات للتغيير”.

We hope to see more of Beirut’s transit champions riding the bus with the likes of us in the near future.

نأمل أن نرى المزيد من الأبطال في بيروت الذين يركبون الحافلة مع أمثالنا في المستقبل القريب

Symposium report prepared by Mira Tfaily, Chadi Faraj and Jad Baaklini

![Cola to Chouiefat [Sara and Sirene]](http://blog.busmap.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/SaraSireneMap.png)

![Cola to Baakline [Rachad]](http://blog.busmap.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/RachadMap.png)

![Cola to Aramoun/Qabr Chamoun [Ali]](http://blog.busmap.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/AliMap.png)