On February 27th, ELARD held a focus group with the general public in the Matn district, at the Saydeh Church hall in Sin el-Fil, as part of their ongoing Environmental and Social Impact Assessment study for the proposed BRT project that we blogged about previously. A good spectrum of views were voiced, and we were pleasantly surprised by the significant number of attendees who already use buses and services-taxis for the majority of their trips (in fact, only one young man admitted to “being a little annoying,” and using his car “for everything,” which was a brilliant way to put it).

We thought we’d pick up our coverage of the BRT conversation again with a brief summary and even briefer analysis of the views expressed in this session:

→ A man who served at the church and identified himself as a law graduate immediately voiced worries about the way the project design would mean “narrowing” the highway along the northern axis to accommodate a dedicated bus lane. He argued that, unless measures are taken to avoid increasing traffic for car drivers or at least prepare them beforehand through awareness and marketing campaigns to know what to expect, there will be an immediate backlash against the project. “This needs to work well from Day 1,” he insisted.

His comments were quite pertinent because they touched on a theme also discussed in an earlier focus group with transport unions (which we will post about in some detail soon): while the BRT project postulates an indirect theory of behavioral change based on speed, efficiency and rational choice — i.e. “when people see a bus running smoothly while they are stuck in traffic, they will think about taking the bus next time” — which seems reasonable on the surface, this comment and others like it point to an underappreciated emotional and maybe even moralistic dimension to this change as well. “People in Lebanon will not react positively to any change if they are not preconditioned through direct appeals to see their personal interest in this change,” he argued, echoing a similar point raised by one transit union representative about the project’s “image.”

→ A student who takes the Number 15 from Sin el Fil to AUB did not think the issue of awareness would be such a big deal, agreeing with the project designers’ hypothesis: the biggest argument for the project is its smooth functioning. She also added that billboards and advertisements could go a long way in preparing people for the change.

As for her existing transit use, the student said that even though the Number 15 is too slow, she prefers using it over having to deal with parking and traffic on her way to university. “When I’m forced to drive, I get angry,” she said. She also enjoys encountering her friends on the bus, as many take the same route. The only thing she doesn’t like about the bus is when they get crowded way beyond normal operating capacity. She likes the idea of having fixed bus stops along the BRT route, as this may reduce overcrowding as well as speed up the trip much more, as the slowness of existing transit tends to be due to all the arbitrary stops that drivers have to make to pick up passengers anywhere along the journey. One young man who came in late to the discussion jumped in at this point and argued that this overcrowding is also due to the incentives that drivers currently have to maximize profit by maximizing capacity: “if they become regular employees of the BRT operator, they won’t keep piling on people.” He also suggested that BRT buses would be designed to have people standing up, unlike the Mitsubishi Rosa models that we’re used to on our roads.

We wish more people who don’t take the bus in Lebanon would realize that overcrowding isn’t always due to there being too few buses on the road (though that is the case on some routes); there is a real demand for public transport right now, every day, meaning that anyone claiming that “Lebanese people will never take a bus” — yes, some people say this — is not basing their opinion on facts.

→ Another young man who goes to work to Ashrafieh by service-taxi, and occasionally takes the bus when heading to Batroun or Tripoli, was enthusiastic about the BRT project. The aspect that appealed to him most was its increased level of safety. He also mentioned how he hoped such a project would reduce the number of non-Lebanese transport workers in the sector.

A few comments in this vein, about “too many foreigners” driving buses, were made by others in this meeting, and in other discussions we’ve had with people about public transport. We think that such views need to be reconsidered, not just on humanitarian grounds, but also by realizing that the transit sector is always the easiest job market for migrants to enter, in any society. This can be seen in cities as diverse as New York and Melbourne, in countries where Lebanese people we know personally have worked as bus drivers and own taxi licenses like everyone else. The real issue in Lebanon, then, is not the identity of transport workers, but the unstructured way that non-Lebanese drivers have become integrated into the sector. This leaves everyone, including migrants, at a disadvantage. But let’s not forget as well that there is a war on our border, and the transport system’s receptiveness to new labor flows has been, in many ways, miraculous.

→ A middle aged lady expressed how much she likes existing buses “despite all their negatives.” Taking the bus puts her mind at ease, because she knows exactly where they go, unlike the less predictable routes of service-taxis. She mentioned taking a bus from Cola to Hasbaya, emphasizing how amazing it is to be able to go such distances with ease. “Why would I drive my car all the way there?” she asked. The aspect of the BRT project which she appreciated most was the punctuality of the bus scheduling that would be maintained.

→ A young woman who participated with her mother also agreed that she feels safer on the bus than in service-taxis. This is a common theme we hear from many women who use the bus regularly; buses tend to be seen as more public than taxis, leading to less harassment. She also added that she supports public transport because its better for the environment and personal budgeting than driving a car.

When asked what she thought the BRT project could add to improve personal safety even more, she said that video monitoring would help a lot to convince more women to consider the bus. The issue of women’s experiences of public transport is very important to us, and we will be publishing a series of posts on this subject very soon.

→ Interestingly, the sole car driver in the group claimed that even though he prefers his car, having taken a bus only once and losing his temper over its slowness, he might also be convinced to start taking public transport if the BRT project proved to be an effective alternative.

→ The final intervention came from a man who identified himself as a plumber and a Syrian who has lived in Sin el Fil for over 30 years. He argued that the new bus system should be run by the state, with existing operators hired by the state (ta3a2od), with social security and a fixed salary that would better their circumstances. It would be interesting to see whether transit unions would be open to such an idea, as their suggestions were more “free market”-oriented in scope (more on this in another post).

→ We asked whether any of the participants would have a problem walking ~500 meters to get to a bus stop, since the issue of bus user behavior was raised in a previous focus group as an obstacle to be surmounted, but the response in this session was unanimous: people are willing to walk to bus stops if this means increased safety for them. We wonder if this would be true for Beirut bus users as well.

→ The last two points of discussion that stick out for us have to do with pricing and geographic integration: When we asked about the expected price of the BRT journey, since there has been some public talk of a 5000LL fare, we were told again that this issue is still being studied: should there be a flat rate or a sliding scale based on distance traveled? We asked participants how much they would be willing to pay for a trip to Hamra from where we were: 3000LL? Some said that this was reasonable, but the law graduate argued for a “fair usage system” that balanced between different social classes and the state’s need to recoup its investment in the project. We wonder what the World Bank’s loan for this project would stipulate in this regard, and whether a real balance can be found in a society with such a stark difference in classes. We tried to make this point during the meeting: that a great majority of existing bus users are migrant workers and retirees, for whom even a 500LL increase could make a significant impact – would the new BRT project create a two-tier system, with the most vulnerable forced to stay in the informally-run sector?

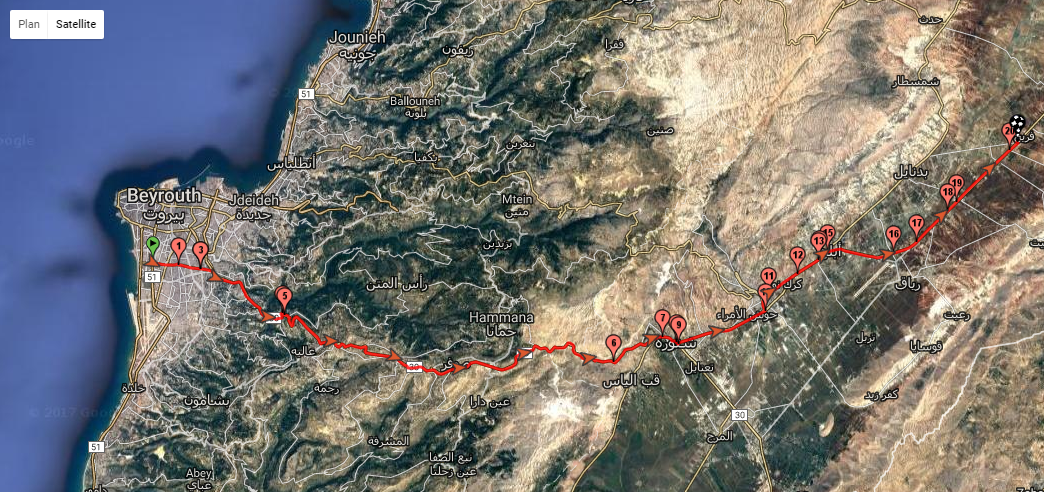

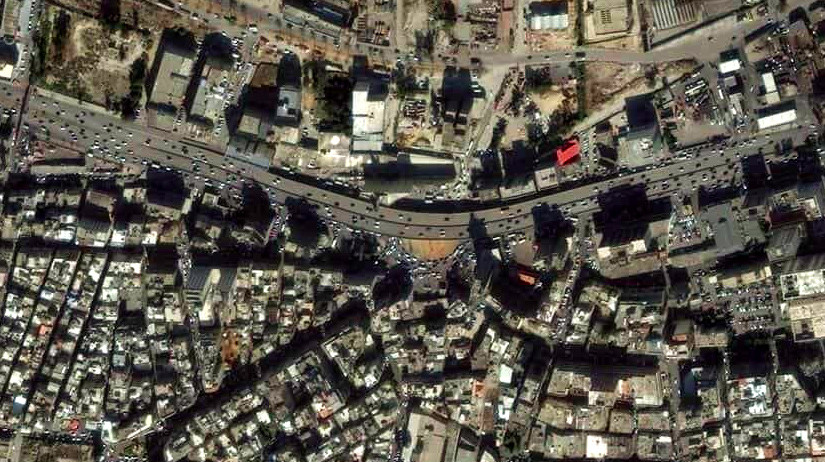

The second issue is equally thorny: the project design as it exists seems to cater too much to the coastal areas in and around Beirut, with suburban residents being left as an afterthought. Even this session, geared towards Matn, focused mostly on the areas closest to Beirut. The ongoing traffic chaos due to construction in Mkalles should raise a red flag about taking the traffic flow from the Upper Matn and surrounding regions too lightly. There are many educational institutions in this area, and morning traffic is a disaster on a regular basis, with far-reaching effects beyond the Matn. The only scenario being presented now, it seems, is: “people coming down from Bikfaya can park their cars [in Park and Ride facilities] when coming down to the coast” — but shouldn’t Park and Ride be encouraged further away from the coast? How many commuters would drive all the way from Bikfaya to the coast, going through all the traffic in that area, just to take a 10 minute bus ride into the city? The incentive to leave their cars at home should be planned for much earlier in the journey as a basic part of the BRT system itself. This is why, we insist again, that feeder buses from the regions surrounding the northern axis of Beirut must be planned for early on for this pilot project to effectively reduce traffic from Day 1; this cannot be left as an emergent possibility we hope will happen once the BRT system is up and running.

Since this project is ostensibly part of a much larger master plan, there is a real opportunity here for the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, the OCFTC and the CDR to work together with local municipalities and transit unions and operators in order to use the BRT project as a catalyst for mobility improvements across Greater Beirut and Mount Lebanon. The way this project is implemented can set the tone for all projects to be developed in the foreseeable future: will it be a form of urban acupuncture that frees up blocked energies and flows making even further improvements easier to attain, or will it be another bandage on a gaping wound?