On International Workers’ Day, we remember and celebrate the often-times hidden labor that keeps our cities running. From bus drivers to sanitation workers, nurses to waiters — we salute you.

May Day is also a time to reflect on and challenge inequality. Attitudes towards public transport in Lebanon are often linked to class distinctions. Sometimes these attitudes are masked behind concerns over cleanliness or timeliness or safety — all of which are consumer rights that are not evenly distributed, and hence, are in themselves class markers; other times, attitudes will be much more direct in their aversion to mingling with ‘people who take the bus.’

Today, we want to share the first contribution to the series of posts on women’s experiences on public transport announced on International Women’s Day by highlighting the intersections of class, race and gender shaping how we get around Beirut. Zahra’s thoughtful story is about learning and unlearning, and the experience of challenging fear and privilege to participate more fully in the urban diversity of Beirut. This is a process that never ends, and requires bravery to face up to ourselves.

* * *

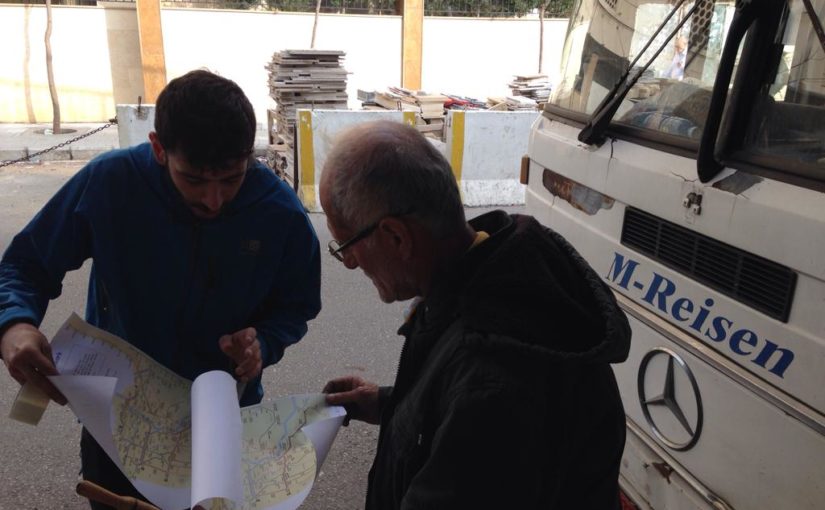

I took my first bus in Beirut under the Dawra bridge, heading north to Byblos on the afternoon of Valentine’s Day with an ex-boyfriend. Neither of us had a car, he was British, and I had recently returned from London, so bus travel was both acceptable and desirable. Before London, I had lived in Lebanon for 6 years but I never set foot on a bus partly because I didn’t need to, but mostly because it wasn’t an option. I was a student at the American University of Beirut and was surrounded by a circle of friends that were both revolted and terrified by the idea of public transport. But the aversion was shared by my family and friends outside of AUB, so it didn’t seem like just an issue of financial means.

Since my (non-voluntary) return from London, I was adamant on crafting a “fresh start” and was driven by preferences and considerations that were detached from the Lebanese context. Exploring options for public transport in Lebanon was a choice taken from a privileged position; it was something quite alternative and enjoyable. Taking the bus in a country where bus travel is not mainstream (to someone like me at least) was my way of living in the kind of city I want to live in, as opposed to the real one I have no choice but to be part of and be oppressed by. And so I repeated this journey of imagination several times and loved it. That day in Dawra, my British companion helped me detach myself even more from the social context and provided me with what I felt was an immunity from social taboos. Being a male, he also gave me a sense of protection, even though I knew that if anything were to happen, I would be the one doing the protecting.

As for first impressions, the first thing I thought when I rode a bus was: “it’s not as bad as everybody thinks it is”. People were ‘normal-looking’… there were women like me… young, some middle aged, Lebanese, and more or less “well-presented” or mratab as they say. This first impression discredited the assumptions that so many people around me held- that buses are run down, stink, full of migrant workers and haunted by the spectre of the dangerous Syrian worker. The second thought that came to my mind was that all these people were acting very normal and civil, including the bus driver. The normality reassured me. I was certainly in a new place, outside my comfort zone, but judging by the looks of the people around me, I wasn’t really outside my ‘circle’ and even if I was, these outsiders weren’t so different. The men were not astonished by the presence of women amongst them, even though some of them were young and attractive and alone.

Once I found comfort in this new space, I was able to sit back and enjoy the ride and this is how the ‘entertainment value’ of the bus came to be my reason to seek it many times after. It turned out that I was an outsider after all because I wasn’t just commuting like everyone else, I was there for the journey. On a bus, I was the audience, and the city was my show. People, conversations, incidents, the humor and absurdity of Lebanese life flashed before me and I was both part of this show and its observer. It created a new experience of the city and a new sense of belonging to a ‘public’ space/facility/realm.

Bus No.2

Bus No. 2 passes right by my house and heads to Hamra as its final stop. Every day, I would see it passing by but always resorted to service taxis, even though they cost me much more (especially given my request to cross the imaginary desert that stood between Ashrafieh and Hamra). The 1,000 lira bus fare was very appealing to an unemployed graduate, so I decided to try it out one day. When I entered, I tried to act like a regular to compensate for the red lipstick and heels. It didn’t work and all eyes were on me, especially when I asked the driver how long the journey to Hamra takes. He wouldn’t give me a straight answer: “it depends on the traffic”. My insistence was holding back the bus so a commuter shouted from the back, “half an hour.” I thanked him, paid the fare, and sat in the back relieved that the ‘gaze’ had broken off and moved on to its new victims. On the way, I was overjoyed to be heading to work on a bus. I felt there was an order of things that I was never aware of in this city… something was working and people were abiding by rules. At the time I didn’t know LCC buses were operated by a private company and thought that they were government-operated. This initial idea however gave me a feeling I have never felt before in this country… that I was entitled to a service as a citizen, that there was a government looking after me, that I was no different than anyone else on the bus, migrant worker, Lebanese, man, female alike.

The bus also took me through neighborhoods I don’t usually go through on my way to work, always seeking the same and shortest route. The bus ride expanded the city’s horizon and it felt like everything was a lot more connected. I got to work in 50 minutes as opposed to the usual 20 something minutes it would have taken by car or service, but it was worth it and I was in a good mood. I haven’t repeated it since because it’s simply not practical to travel for 50 minutes. If that wasn’t the case I would gladly drop the service and car rental for the bus.

When we reached the final stop in Hamra next to Barbar, everyone was getting off and the driver noticed that I was confused so he asked me where I am going. I said I was heading right to the end of Hamra and asked if the bus heads in that direction. He said no so I politely thanked him and left to continue walking. As I headed off, the bus driver started beeping at me so I turned back to see if I had forgotten something. He told me “if you want I can drop you, just for you, walaw”… and so my experience of utmost equality came to an abrupt end and back I was to the city of preferential treatment, sweaty wrinkled winks and catcalling. I said no thank you and walked off doubting whether I was too harsh in my initial reading of the gesture. Maybe he was just being nice, can’t people be nice? Do we have to be programmed like Londoners? I yearned for the predictability I felt for 50 minutes while on the bus no.2. I may have made up this predictability entirely, it may have been just my projected expectations of what a public transport system should be like. Maybe another person would have appreciated the driver’s offer. Who am I to say? I now ride to work in my rented car.