On August 22, a campaign based around the ongoing waste (mis)management crisis in Lebanon became much much more. The movement called طلعت ريحتكم struck a chord with people across Lebanon, and brought thousands into Riad al-Solh Square to voice their anger over a wide range of policy failures and socioeconomic issues. At the center of this discontent is the generalized syndrome of deadlock in governance in the country, but others have gone further in their diagnoses. Many have focused on the endemic culture of nepotism and corruption among the semi-feudal political class ruling the country. Others have struck at the root, focusing on the confessional system itself as the perpetual engine of division, unaccountability and immobilism. Others have dug even deeper into the capitalist system as the context of contexts for our problems.

In the days that followed that fateful Saturday, several factors have pushed and pulled the movement in different directions. First, there was the inexplicable and inexcusable state violence against protesters, which fueled anger and encouraged more people to join. Second, there were the fears of party-orchestrated infiltration and sabotage, and the resulting controversy among movement supporters over the classist and sectarian overtones of these fears, and the ways that protest organizers chose to respond to them. Finally, there was the plurality of proposals and counterproposals for the way forward with movement demands, stemming from the various criss-crossing analyses described above. By August 29, the movement grew far beyond its initial scope and framing as #YouStink, and became a true platform for mass political action.

Today, a host of inspiring groups, new and established, are active “in the square” — community-based campaigns like عكار_مش_مزبلة, citizen journalism projects like أخبار الساحة, recycling initiatives like Sar Lezem Rassak Yifroz, anti-capitalist fora like المنشور, student organizations like AUB Secular Club, and advocacy networks like National Campaign for Sustainable Transportation, etc.

This means that the visions, missions and approaches are now many. Where do we go from here?

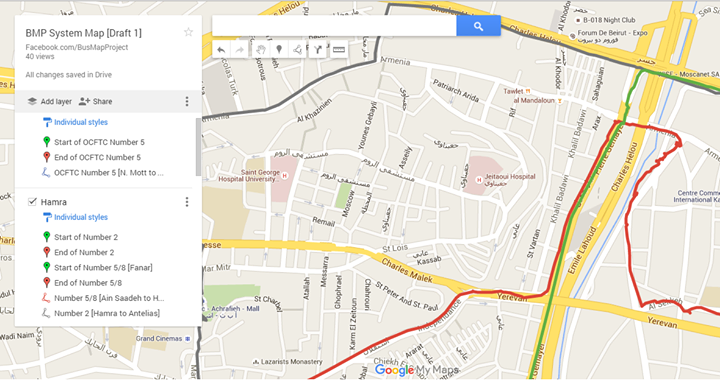

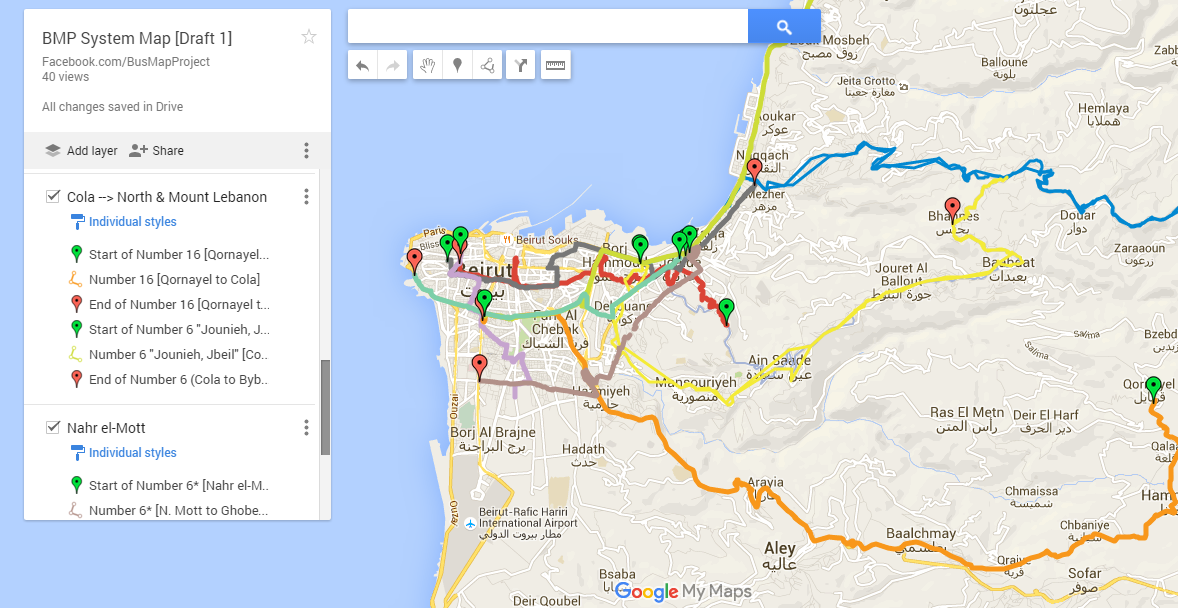

Bus Map Project was conceived as a modest, small-scale intervention in the gaps between state neglect and policy-oriented advocacy. We chose a pragmatic approach that strategically set aside the twin issues of rights and demands. We stubbornly focused on the present — on the bus system as it exists today, without quick judgement or dismissal — because we felt that other pro-transit campaigns have either focused too much on the past (e.g. the state’s neglect of public transport) or too much on the future (e.g. a desired public transport system). More fundamentally, we chose an approach that would bypass the state altogether — with or without a president, with or without a parliament, with or without a responsive Ministry of Public Works & Transport, we want to begin collectively building our own tools that help us make sense of and navigate our cities.

We support the current climate of protest. We believe that more awareness of the systemic problems that produce so many failures across so many sectors — from housing to transport to the environment — is important. Our project has only just started, but we wish to contribute to this ongoing conversation sparked by #YouStink by calling for more small-scale, closely-allied, locally-based, and non-state reliant projects focused on the tail-end of the crises created by Lebanon’s broken system of governance. The movement’s broader slogans — anti-corruption, secularism, electoral reform, parliamentary renewal — are of vital importance, but we believe that Lebanon also needs solutions in the here-and-now. We need better representation, better institutions, etc, but we also need less dependence, less centralization, less delegation of our power to connect and work together as civic actors.

This is not a call to “de-politicize” the movement — that is impossible. It is, however, a plea for more fidelity to the immediate, to the concrete, and to ourselves. There is strength in numbers — a single-issue campaign acting alone will struggle to accomplish anything, but a sustained and focused project acting within a broad network of supportive campaigns is more likely to succeed, for the benefit of all. Yalla.

If you are interested in learning more about how you can help Bus Map Project, please do not hesitate to contact us.

#مستمرون